|

|

| |

|

instep

profile

A Pakistani filmmaker in Hollywood

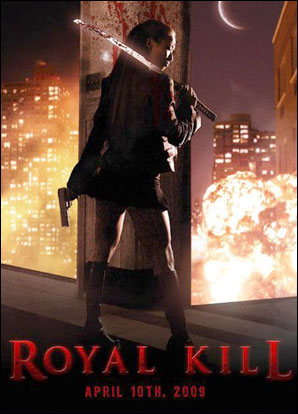

It's not easy to make it in the big league but Babar Ahmed is resolute that he will. His second film Royal Kill got a theatrical opening in America. It's a big achievement from one of our own. Here is what it takes...

By Anindita Ghose |

| |

Independent filmmaker Babar Ahmed is twice removed from Hollywood's ideal: He is a Pakistani Muslim and lives in Washington D.C. His first script meeting with a mid-sized Hollywood studio unfolded so terribly that the studio was hesitant to even reimburse his airfare. This was ten years ago.

In the film industry, a decade is a century. Ahmed hasn't been very prolific: Until recently, he had two short films (Mother and Son, 1997; Bittersweet Mangoes, 1998) and one feature Genius, 2003 (released on DVD) to show. But he is bright-eyed. He doesn't wear the aura of a frustrated artist. His latest feature release, Royal Kill, is the lowest budget film ever to be released by AMC theatres, a theatre chain in the United States that released it across five screens in the country. The indie film's run was even extended to a second and third week from its initial one week schedule. The psychological thriller features an eclectic cast: Academy Award nominees Pat Morita and Eric Roberts, WWE Women's Champion and wrestler Gail |

|

|

Kim,former Calvin Klein model and amateur boxer Alexander Wraith and Disney sweetheart Lalaine of Lizzy McGuire fame. The fantastical story revolves around an oblivious young heiress (Lalaine) from the Himalayan kingdom of Samarza. Lalaine plays a regular High School kid in the Unites States who is oblivious of her royal lineage and the narrative develops with her planned assassination by a fearsome warrior (Kim) and her royal guard's (Wraith) struggle to protect her. |

|

| When I first meet Ahmed in Washington D.C in December, he is getting ready to fly off to Los Angeles to meet with an agent who is interested in collaborating with him on the recently finished Royal Kill. The movie has been a long time in the making and Ahmed cites funding as the underlying reason. He believes that the unfortunate fact that this is Pat Morita's last film appearance - he passed away in 2005 soon after he finished filming the project - might work in the film's favor. Karate Kid fans who remember him as Sensei Miyagi in the cult series, might be drawn to Royal Kill in video stores if only to see him take his last bow. |

| |

| Ahmed appears to be balancing precariously on a metaphorical fence. On one side, there is that elusive playground of indie success stories and on the other, a backyard of bitter tryouts. His feature debut, Genius, won him three festival awards. Not Sundance or Locarno, but ones much smaller in scale-Valleyfest, Park City Film Music and the New York Indo-American Arts Council Film Festivals. But Ahmed was interviewed by BBC World and NBC4. And Variety magazine, in a DVD review, described the end twist of Genius, a film about a dyslexic African American teenager and his relationship with his teacher, as an "impressively orchestrated zinger." The film trade publication also predicted the film's future as an indie theatrical release or "black-themed cable." It had neither. But Ahmed is somewhat proud of its nationwide release in more than 2000 home video stores (Delta Entertainment, MTI Home Video). The figure, while being the norm for thrillers and action films, is impressive for an indie drama, which is usually a tough sell. The movie also has its fair share of favorable user reviews on IMDb and Netflix. But while some indie video releases manage to elicit reviews from mainstream film critics, Genius didn't make that cut. |

|

|

Remarkable in its technical aspects - the cinematography and music is brilliant - Ahmed's debut lacks that quintessence of indie movie aesthetics, the strengths of which usually lie in story, dialogue and evocative performances. Instead, Ahmed puts together a potential commercial blockbuster, only a thousand times smaller in scale. It is evident that he thinks big league. When I ask him who his favorite filmmaker is, he doesn't name an indie genius, but evokes Stanley Kubrick instead.

The 30 something filmmaker's career trajectory isn't one with sharp angles. It connotes tempered choices and a move towards a one-dimensional goal, mirroring the man himself. By indie standards, he is already old. He is the odd one out amongst the pot smoking, craggy haired, eclectically dressed creative characters that populate the indie brigade. When we meet for dinner, at Sette, an Italian restaurant in downtown D.C. that he chose, he is wearing a blue jacket, a blue Russian shapka and a blue checked scarf. When he finally takes his |

|

| jacket off (he seems comfortable with everything on till I'm halfway through my entrée) I see a button-down shirt. He transcends all possible stereotypes of wild child film artists: He lives with his parents, is married to a banker and doesn't hold an academic degree in filmmaking. In fact, with an undergraduate degree in economics from University College London and an M.Phil in development studies from Cambridge, one might wonder what he is doing behind the lens at all. |

|

His proverbial moment of truth occurred when he was offered a position as a PhD candidate at Cambridge. Life seemed all set. And yet for someone who has always followed conventions, it seemed like a dreary proposition. A vacation beckoned and Ahmed enrolled for a four-week basic summer film course at the New York Film Academy for precisely that-a vacation. Prior to this, Ahmed had a few faltering forays as part of a film society in high school and at a one-day course at a technical institute in London. He was 18, just out of High School and had seen the eight to five course advertised in a newspaper. He had arrived there at 7:45 in all sincerity. The instructor had showed up at 10 and a few more students had trickled in later to sit around a malfunctioning camera.

"It was most frustrating," he says with an odd nostalgic smile.

Understandably, with this false start, he wasn't expecting much from his American film sojourn. But the introductory talk at NYFA itself caught his fancy.

"The teacher quoted Macbeth and made filmmaking seem to be something more than art: It was about life, about influencing ideas. It was what the British economist John Maynard Keynes quoted often in his works: 'Ideas shape the course of history'," he recalls.

The following summer, he enrolled in another a summer film workshop, this time stepping up a notch to the Tisch School at New York University. |

|

Talking to Ahmed is like trying to follow at least three trains of thought at once. You manage to climb aboard one and think you're going somewhere, but he drops you off and before you know it, you're heading off in another direction. But when he vaults from Shakespeare to Keynes, it doesn't seem pretentious. The physicality of his school boy looks-the clear brown eyes and noble, sculpted features-educe belief.

Ahmed orders his dinner without seeing the menu. It is a seafood dish, something he's had before. In his creative choices, he displays more spontaneity. He believes that the script is just a blueprint and has often irked his collaborators with last-minute changes. Kenneth Lampl, who scored Royal Kill, recalls how livid he was when Ahmed suddenly decided to change a pivotal plot point after the final score had been composed. |

|

|

| |

I had to redo the music, which had been a labor intensive, elaborate process and was surely annoyed. But when I saw the new edit I knew it was the right one - with film you just know - and I really couldn't be angry anymore."

The young filmmaker seems to work with a peculiar combination of spontaneity with doggedness. He has been working on Royal Kill since Genius released in 2003. The preproduction was an exhaustive process, and he did it two times over.

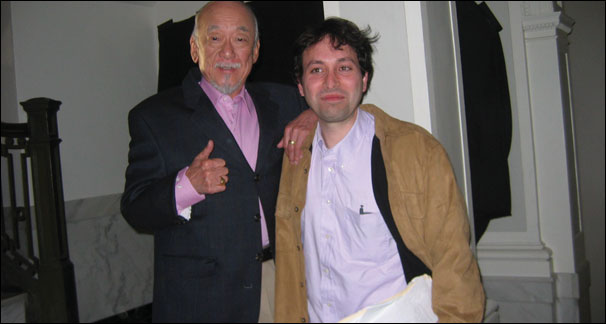

"Pat Morita was the reason the movie took off the way it did. We were close to shooting and had a tentative cast lined up when an old friend I'd contacted earlier called me out of the blue and said we were on a three-way line with Morita. It was one of those moments," he says.

Soon after, Eric Roberts and Gail Kim came on board and the entire production was ramped up in scale. Ahmed decided it made economic sense to stretch the storyline from its Asian setting to an international one.

Ahmed has lived an international life himself. Of his 30-something years, Ahmed has spent roughly one third in Pakistan, England and the United States. He is the second of four children. His elder sister teaches at Cambridge and runs an interfaith center at the university. His younger brother is a recent law graduate from George Washington University and his youngest sister is a freshman at Georgetown University, both in the United States. Growing up, he admits he wasn't a very arty child.

"I was more into sports and academics. I wasn't even so much of a film buff but I've always been fascinated by all forms of creative expression," he says. |

|

|

|

If he once had a British intonation, it has faded after seven years in Washington D.C. He's been uprooted numerous times, because of his father's job as a Pakistani bureaucrat who had to move his family around for work. And his films reflect this global lineage. The early short, Bittersweet Mangoes, is about a homeless Hispanic boy in New York City; Genius deals with an African American teenager and Royal Kill is set in an unidentified exotic land - a far cry from themes generally explored by South Asian filmmakers.

Ahmed is determined to go past clichés.

"Stories of abused teenage boys and women finding their place in society need to be told - but so do many others. Every filmmaker from a developing country cannot be expected to make films on such themes," he says with apparent angst.

Genius, he says, was the first American movie made by an all Pakistani team. The cast and some of the crew was American but the director, producer and financers were not. It is paradoxical, in fact, that his predisposition to cover global themes stems from an innate pride in his own heritage. Pakistan isn't a country that has received very good press of late, especially since 9/11.

"When one Pakistani, or one Muslim, does something terrible it is repeatedly analyzed and reported and used as an example for the entire community. The good is more often than not ignored," he says.

He does not want to counter this phenomenon with propaganda films that try to balance this negative portrayal by reinforcing images of extreme Islamic goodness. Instead, he wants to address the issue by being a "regular filmmaker who makes films of regular issues." He wants to fit in. |

|

Ironically, Babar Ahmed, the guy who wants to fit into American culture, shares his name with Babar Ahmad the British terrorism suspect, the guy who ostensibly wants to make a statement of his religious beliefs. Both "Babar" and "Ahmed" are not very unusual as Islamic names but the uncanny similarity goes beyond their names: Both are Muslims of Pakistani descent, they're in their 30s, they have three siblings, they studied in London and their fathers were civil servants. The suspected terrorist has been incarcerated by the British authorities since August 2004 and is currently fighting extradition by the American government. Ahmed confronts my observation with restrained amusement. He's now been taken off the no-fly lists but it was quite an ordeal for a while, especially right after 9/11. He didn't feel particularly persecuted though.

Unlike the U.K where you can feel an undertone of racism in every interrogation, I never felt insulted through the extra round of |

|

|

| searches at American airports. They were just officials doing their jobs. I was politely told that I'm on a high-alert list and warranted extra scrutiny. It wasn't difficult to respect that," he says. |

| |

Quiet and passive in social situations, Ahmed is didactic on the sets.

"Disagreements on the set are good," Ahmed asserts.

According to him, they denote a level of passion and involvement.

"I favor a disagreement-friendly atmosphere. On a film set, there are several arguments through the day between the director and actors, the actors with each other, the cameraman and the sound person, the costume department and actors…when I hear someone arguing about whether the trousers in a particular scene should be black or blue I feel reassured that I'm working with a committed bunch. Of course, one has to be careful not to let this bruise egos."

In the past, he has taught an honors program in film at George Washington University. And Alexander Wraith, who summer of 2000, Ahmed had called him to an address in midtown New York, near the United Nations building. It was his first film audition and Routh, a college student, was nervous. As he was approaching the address he'd scribbled on the back of his resume, he saw a large group of people circling around "a nice looking guy of average height." Routh recalls his initial feelings: "It was a really hot Saturday. I was confused at first but when I saw a mini camera I realized that this was it. I thought this guy was out of his mind for auditioning actors out on the streets."

Routh contemplated turning back but was persuaded by an attractive production assistant who came up to him to sign him on the roster. "I couldn't be more glad that I stayed on. I realized that this was his way of testing his actors' caliber and I was impressed. It turned out that he was impressed by me as well and so he called me three weeks later for some test shots."

Routh had another short film on offer but it was easy to choose between the two: "I was excited about starting off with a guy like that."

If Babar Ahmed were a film, he'd warrant a "G" certificate almost immediately. For a drink, he settles for a Diet Coke (At coffee shops, he opts for fruit juices). An occasional sliver of dry wit slips through his otherwise serious persona. Something to speak for all the years he spent in England. He tells me he reads the Alaska Star and that he's learning how to knit (because that's what people who read the Alaska Star do). And I crinkle my eyes because it is difficult to imagine a joke from the straight-faced person who was spouting group psychology theories a minute ago.

Cinematographer Jonathan Belinksi was several years senior to Ahmed at NYU. After graduation, he branched out into the lucrative route of photographing advertising films and big league sports games. It took some convincing from Ahmed to bring Belinski on board for Genius and to work for fees much less than what he usually charges.

"It's not like I knew him very well at NYU and I couldn't understand his ideas at first. They were unorthodox, overly complicated and he wasn't offering to pay me much. But he won me over. He can do these things somehow."

Belinksi is one of the few people who has worked with Ahmed on both his features. He thinks his young colleague has matured over time and is more open to ideas now. "But with that, his stubbornness has increased as well," he smiles.

Belinksi recalls an incident while shooting the final montage of Royal Kill: "I put my foot down because I was quite sure we wouldn't be able to pull it off in the location Babar had picked. It was way too grand. But that guy has some tenacity despite his quiet demeanor he egged me on."

In 2003, Ahmed had his first screening in front of a large audience. I ask him if he was on edge to which he responds simply: "I'm never on edge."

It was at the Islamic Society of North America-the largest Muslim organization of North America with centres in Chicago and Washington D.C. "There were a total of 30,000 people attending the cultural festival. The audience was happy that I hadn't made another movie dealing with the semantics of the burkha or men who beat their wives."

Spouting film trade jargon and talking of film markets and genres that "sell", Ahmed appears to be an astute businessman. His first feature-a drama-was a tough sell but with an action-packed thriller on his hands now, he opted to play safe. He shares how he planned Royal Kill's release: "We struck the video deal for Genius so soon that we couldn't incorporate its reviews and star ratings on the DVD. This time, I'm going to be more cautious. Waiting helps."

While independent filmmakers rely on film festivals for recognition, he brushes them aside saying that they mean very little when one is facing a mainstream audience.

"Festivals are good for the filmmaker's pride and they can definitely help first time directors. But beyond that, if a festival can't help your film secure a release, what's the point?" he poses rhetorically.

Ahmed, the potential doctoral candidate who deferred his PhD program at Cambridge one semester at a time for two years before he decided that cinema was his calling, knows how to take small steps. He probably won't crash into the Hollywood scene overnight. But one toe at a time, he is already inching in. |

| |

|