|

|

| |

instep

overview

Peshawar underground:

It's difficult to be a rock star in the land the epitomises

conservatism, yet something shocking is happening. There is a

rock scene waiting to burst out of the NWFP. Rahim Shah was just

the beginning, Sajid and Zeeshan were proof that originality can

spring out of unlikely places and there are others who are making

their riffs and ragas heard... slowly, but surely.

By Maria

Tirmizi

|

| |

Young

blood

Jehangir Aziz is only 17-years-old. Yet, his song 'Never Change' has

already been nominated at a music award show. He's been singing, writing

and composing since he was 12 and is famous for being one of the youngest

grunge musicians in the country. When he put the song up on websites

like SoundClick, he claims to have received numerous offers from international

communities for using it in their films.

Shahab Qamar and Nazeef are 21. Through their band Avid, they are

trying to give birth to a genre that they call "e-rock"--specifically,

electronic rock, using audio synthesizers with rock and orchestral

instrument. So far, they have recorded four songs ('UET K Café

Mein', 'Tanha', 'Waday' and 'The Last Mile') in their own mini studio,

winning first prize in an intra-college singing competition because

of their unique, original songs. |

|

Mohsin Kamal is the president of a music society called Metal, which

arranges interschool music competitions to promote talented musicians

and has also taken Pakistan to India, making our country shine in

all its original glory in a festival across the border.

All three have something startling in common: They hail from a land

of billboard-burning mobs and bearded men in power - the land of the

MMA, Peshawar. |

| |

Two

sides of Peshawar

In all fairness, Peshawar is, of course, not all about the MMA. You

have mouth-watering chapli kababs and famous cloth markets thronged

with women bargaining vociferously, lest their cloth-draped heads

be mistaken for meekness. There's the famous Chief Burger/Pizza no

one seems to get over and beautiful sea-green eyes everywhere.

But there are also billboards conspicuously deprived of female faces,

an ancient looking Ferris wheel in a dilapidated amusement part revolving,

for the most part, bearded men in brown sharis (shawls for males)

and an exactly zilch number of fun, public places where a young crowd

can just chill out at.

And beyond all that, you have melodious rubabs and sarangis soaring

flowery Pushto poetry at lavish weddings, with clamorously happy intermingling

between family and friends, and dancing carrying on late into the

night. Add hard rock into the mixture because of the inevitable youthquake

that no city is eventually safe from, and you have Peshawar, a perfect

blend of a rich, colourful, somewhat misjudged, and of late troubled

city |

| |

The

rise of Sajid and Zeeshan

One duo that has been able to make it through all the barriers that

Peshawar has begun to represent is Sajid and Zeeshan, now nominated

for the Lux Style Awards in the Best Album Category for their album

One Light Year at Snail Speed. Their music truly demonstrates that

given a chance, the city does have something unique and significant

to offer.

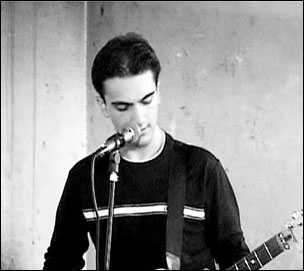

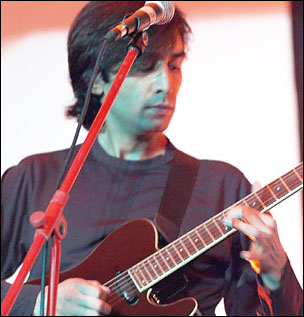

Zeeshan

Pervaiz is the talented, cheery faced music producer and video director.

Sajid Ghafoor is the brooding guitarist, lyricist and composer with

the haunting, silky voice. Together, the electronic virtuoso and the

alternate rocker, meeting back in 2001, brought forward a true novelty--

an English rock album from a city which, in their own words, has placed

a tacit ban on most forms of creative expression.

|

|

| |

Their

journey, poignantly chronicled in their video of 'My Happiness', starts

from the mid 90s when two brothers, Sarmad and Sajid, officially kicked

off the underground rock music scene in Peshawar with their band called

Stills.

"Sajid and Sarmad were the first to encourage people to pursue

music in Peshawar," said Zeeshan while talking to Instep. "They

played at the American Club, started doing covers around town, even

performed outside Peshawar in cities like Lahore. Their gigs, and

also those of another band called Opiate, were always very well-perceived."

Luckily, along came various music channels that started giving projection

to different bands from around the country, and things got a whole

lot more exciting. Pakistan started springing out so many young, self-made

musicians who remained true to their soul, that it literally brought

India, with all its gigantic budgets and bare skin wiggling tactics

to shame.

"It looked like the projection scene would get bigger,"

said Zeeshan. Even in a place like Peshawar.

And then elections happened.

"Unfortunately, MMA put a ban on general artistic expression,

discouraging a lot of people. When there was no association with art,

some people even turned to drugs in their hopelessness," he continued.

Despite that, the duo Sajid and Zeeshan decided to fuse their areas

of expertise to revive music from a city that had basically, but not

overtly so, banned artistic expression. They started performing at

gigs in other parts of the country, specifically Lahore and Karachi,

stupefying their fast growing number of fans who had to ask twice:

they're from WHERE again?

"The reason our music gets recognized is because it's in English

and it's from Peshawar," says Zeeshan. Not denying the novelty

factor Peshawar adds to their image, their music is good enough to

have won accolades even if it came out of one of the three main cities.

|

| |

The

plight of playing music in Peshawar

According to Zeeshan, the status on the music scene in Peshawar as

of late is that there is no music scene in Peshawar.

"The music scene here has not developed as such. There are only

sporadic bands here and there. There's Jehangir Aziz who is very talented

and one band called Az, for whom I'm producing a couple of songs.

Most of these kids are really young, around 20 to 21 years old."

Students. Apart from their primary priority of education, they have

an extra burden of being stuck in a deeply conservative society that

doesn't look upon musicians as anything more than 'mirasis'.

Zeeshan calls such a label 'a social evil.' |

|

| |

Shahab,

the talented 21-year-old from the band Avid says, "Out here,

they call music 'Damtoab', which is like an abuse in the Pakhtun culture.

They think playing music basically diminishes a family's pride and

honour."

Talking about his own music, Shahab endearingly refers to himself

as the Zeeshan of his band, and his fellow musician, Nazeef, the Sajid

of the equation. "Nazeef is the vocalist and guitarist (rhythm/lead)

while I am responsible for the bass, drums, keyboard, synths."

He feels that although the popularity of 'Ya Qurban' type Pushto songs

are slowly and steadily being replaced by upbeat techno and remixes,

there is still very little scope in his hometown for rock music.

The first reason for that is of course language. |

| |

"With

majority of the city speaking Pushto, people's sentimental attachment

to their mother tongue directly or indirectly affects their taste

of music. They think rock music is nothing but noise," he says.

He also points out that being students, parents are unwilling to spend

money on musical instruments, thinking that it would distract them

from studying. And there are no quality instrument shops in Peshawar

as well.

"The shops here are just looting inexperienced customers and

many youngsters have no choice but to turn to the famous Bara Market

for secondhand substandard instruments," says Shahab. |

|

| |

Talent

rocks on

Jehangir Aziz, the other incredible musician from Peshawar, recalls

the first time he performed in public at the American school.

"We used to have a lot of opportunities back then to go up on

stage and give it all. I also performed at the British Council; it

was then that everyone actually acknowledged rock music in Peshawar."

"Recently I was selected as a judge in a music competition held

in FAST University. One could easily see the talent Peshawar has that

day. Basically, the musicians over here aren't given much to work

with because of the conservative attitude from people," said

Jehangir.

Mohsin Kamal, President of the Peshawar-based music society called

Metal told Instep: "If you could only hear Jehangir perform live,

you would be amazed that someone from Pakistan at such a young age

can sing an English rock song THAT good."

But not a lot of people are aware of this talent coming from the frontier

region.

Sajid Ghafoor (of Sajid and Zeeshan) told Instep: "No one knows

about musicians in Peshawar, but they're really good. Kids like Shahab,

who're mostly into rock, are very talented. But it's still a new thing

for Peshawar."

Musing

over the boredom in Peshawar, and knowing that his own English rock

album has a very niche market, Sajid says, "You can't ever expect

rock to capture a commercial crowd in a country like Pakistan. Just

look at the literacy rate here," he says almost in disgust.

"Most people are biased against English as it is. When you don't

understand something, you tend to dislike it. Presumption is the mother

of all screw ups. So one has to contemplate then - is Sajid and Zeeshan

a stupid idea?"

Replying to his own question with an emphatic 'No', he proceeds, "We

are doing it for US. If I wanted to make more money, I wouldn't do

music. This is for our own sense of personal achievement."

And why does he stick to English despite the bias that he feels exists?

Sajid answers that with four succinct words: "Why the hell not?"

"I feel comfortable with English. Culture is basically following

your own comfort level. I wish I felt more comfortable with Urdu but

your accent should be spot on, and I feel mine isn't. Western music

for me has such rich variety," said Sajid.

Even so, a Pushto rock song called 'Lambay' is about to be released

soon by Sajid and Zeeshan. Although the song could end up being admired

by an even 'nich-er' market, the idea sounds so fresh and exciting

that one can hardly wait to hear it.

|

| |

Music

under fire

For a full-fledged music scene to develop in a city, one obviously

needs the right venues for practicing and performing. Not only does

Peshawar seriously lack those, but even contemplating to open up such

places seems to be a dangerous idea because of the recent spate of

bombings and volatile mob tendencies.

A few months back when Atif Aslam was supposed to perform at Pearl

Continental, Peshawar, one of the very few places that can actually

guarantee security, a bomb threat started circulating around town.

Mohsin Kamal, whose band was supposed to open the act for Atif, was

seriously disappointed when the concert was cancelled due to security

concerns.

No doubt, performers have to skeptical about going to Peshawar when

even Sajid and Zeeshan, being born and bred in the city, have not

had a single concert as a duo in their own hometown. |

|

| |

Secure

venues like Pearl Continent or the Golf Club are way too expensive

for an underground band. Then there are the popular Army organized

concerts, which although highly safe, tend to solely concentrate on

popular, commercial artists, not emerging rock musicians.

"There are seriously speaking, no venues for musicians to perform

at. And I surely hope that there would be a platform for talent because

in a place like Peshawar, it's so easy for such art to be ignored

and eventually wasted," Jehangir said

"It's been ages since we've had a public concert here in Peshawar.

As far as young musicians are concerned, they generally perform at

their university functions, fun fairs, parties, that is, if their

university supports them," says Shahab.

Mohsin Kamal feels that inside universities, there are no problems,

with no one trying to break up any event, even if it is music-related.

But in public places like open parks, you just cannot guarantee anything.

But Shahab feels that there are issues inside universities as well.

"There exist political student federations in most of the universities

of Peshawar who are severely against musical events. Several incidents

are known when they tried to spoil and stop such events by force and

even carried out physical violence against those who participated

in them. This has not just created a fear among the students but also

the university administration. They no longer provide funds for entertainment

related societies since they are unable to guarantee student protection,"

he says.

Branching out to the Lahore-Islamabad circuit

Adding a bright note in the dismal picture, Mohsin says that Masoom's

Cafe has recently opened up in Peshawar and Jehangir has had a talk

with them to allow him to have some gigs over there now and then.

Besides that happening, if it does at all, kids like Jehangir and

Shahab hold a lot of informal gigs inside their homes only for their

family and friends.

"Unless you'd want to invite the MMA along to make it OH-SO much

more exciting," Jehangir adds with sarcasm.

They also try to perform outside Peshawar whenever they can. Jehangir

recalls playing at Civil Junction in Islamabad and being taken aback

by the massive response from the crowd and the level of interest shown

in his music, giving him, what he calls, a serious gig high.

He says, "There are a lot of musicians around who can actually

play and make sense out of what they are doing if only they are given

the opportunity. I don't think they are given much to work with as

they are all trying to stick to the system and gain its approval.

The system is made to not encourage such an activity. Only the really

driven can actually ignore such a response and continue with their

work. Things are changing because of the music channels, but it still

seems like it has a long way to go."

It sure seems like it has a long way to go, long and as far away from

Peshawar as possible, for some musicians at least. Many have moved

out from the volatile terrains for greener pastures. The lead singer

of Lagaan is originally from Peshawar. Wasim Kamal, prior drummer

of Rungg, and now a part of Lahu, also couldn't stick around in Peshawar

any more.

"When I started my career, all members of my previous band Rungg

moved to Lahore. We knew there is no music scene in Peshawar. There

is talent for sure, but no nurturing of it. I was amazed to see the

difference outside Peshawar, especially in Islamabad, where fellow

musicians alone gathering at normal gigs number at around 200,"

said Wasim.

If there are so many issues in a city like Peshawar, why doesn't the

highly talented duo, Sajid and Zeeshan, just move out? The answer

is obviously very simple. Home is after all, home, and they say moving

out is just not an option. |

| |

Home

is home, even if it is Peshawar

"It's a hindrance, yes, but we just can't leave Peshawar,"

said Zeeshan.

He doesn't find any restrictions on working from inside his house

in his post production studio and is quite comfortable in his hometown.

He also feels that despite the problems, kids are catching on, making

music inside their homes and getting together for informal jams with

friends and families.

"There

is immense amount of potential in Peshawar. Ali Noor has said that

the crowd here is amazing. Junoon used to come here... there used

to be a mixed audience. People are dying for entertainment…

if only the elders here recognize it! A lot of people want to pursue

their interests but the traditional community just tries to sway them

away", says Zeeshan |

|

| |

| And

Shahab has some inspiring last words too. "Things are changing.

There are many others like us who are desperately fighting against

all the odds. We have friends like Mohsin Kamal at universities who

have setup music societies on their own and are providing platform

for youngsters to perform. Meanwhile, Sajid and Zeeshan and artists

like Jehangir Aziz visit such platforms often and guide us in the

right direction for all the right reasons. There is a huge amount

of talent in Peshawar… it's a kind of musical evolution –

which is obviously, a matter of time." |

| |

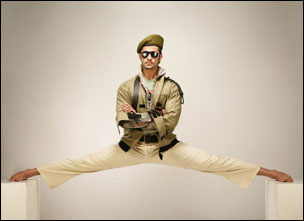

Hotstepper of the week

Ismail Farid |

| |

| When Ismail Farid's

fashion shoot came to Instep (pages 36-39), we knew there was something

extraordinary about this young designer. The crisp clarity of the

shoot and the way it juxtaposed a modernist's vision with cultural

artifacts from Pakistan's traditional heritage alluded to an artistic

mind. It was nothing like the 'beautiful' bridal shoots most designers

prefer to invest in these days; rather it was a bizarre style statement

that oozed oodles of confidence. Model Nausheen Shah had been draped

in a man's clothing - right from the voluminous folds of a starched

white shalwar to the perfect pleats of a churidar - and the images

were striking. After three years in the business, Ismail Farid is

launching his eastern line and when shooting the collection, he had

absolutely no qualms in dressing a woman in it. |

|

| |

"I

was quite sure Instep was calling to reject the shoot," he smiled

when we met two days later. And he explained how, after bouncing the

idea off so many different photographers only to be discouraged that

the idea would bomb, he had clicked with Rizwan-ul-Haq. "Our

thought process is quite similar," he added, "and when I

told him the concept, he understood what I was trying to do."

Ismail Farid may be a lesser known name on the loud and vibrant fashion

scene these days, but he's actually been around for a couple of years,

successfully operating from the much coveted Karachi high street,

Zamzama. He designed Shan's wardrobe for the Asim Raza directed Indigo

campaign and the entire wardrobe of costumes for Najam Sheraz's Mobilink

video, every folk dancer included. Unconventional in his projects,

Ismail has also designed Humayun Saeed's wardrobe for the currently

playing film, Mein Ik Din Laut Key Aoonga. Though the film isn't doing

incredibly well, Ismail's projects evidently have, as he has been

nominated in this year's Lux Style Awards for Best Emerging Talent.

|

| |

We met at Ismail's

shop on Zamzama, which like the rest of the city, was under the rigors

of renovation. He explained how he was adding another floor for his

office and easternwear display as the previous space was turning out

to be insufficient. He'd make do with this and then branch off to

either Park Towers or The Forum as soon as his number came on the

endless waiting list for both malls. Lahore, he admitted, wasn't a

potential market for him yet.

Walking away from the deafening sounds of wood being hammered into

shape, we settled down at Costa and I tried evaluating what had kept

this creative spark away from the fireworks.

|

|

| |

There

were no signs of the hyperbolic overexcitement that one tends to associate

with young fashion designers these days - no visible body piercings

(not even an ear stud), no tattoos, no groomed eyebrows, no experimental

fashion statements and not even a mad cap and colored hairdo. Here

was a perfectly ordinary, good looking and conventionally dressed

young boy who didn't use the endearment, "jaani" even once

in our conversation. He seemed almost shy in comparison to his contemporaries

of the aggressive fashion industry of today.

Ismail explained that he had deliberately not stepped onto the powerful

machine of marketing and branding that has become a necessary part

of owning a fashion label these days. He hadn't, and yet his credentials

were all spanking perfect.

"I've chosen to stay away," he stated without hesitation.

"I'm not a party go-er and don't have much in common with the

average fashion designer these days. I decided I wouldn't fit into

the scene and so stayed out of it." |

| |

| He may have nothing

in common with the fashion icons Pakistan has generated but Ismail

sure has the sensibility and talent to go places. Five years ago,

equipped with a business degree from CBM Karachi, he decided to revert

back to his love for art that had gotten him an A in his A levels.

It's just that art, to him, pointed towards fashion. Taking strength

and then branching off from his family business that already dappled

in textiles (his brother owns DIAZ Tex, a knitting unit in Canada

that supplies to souvenir stores at Disney etc), Ismail ventured into

his own designing. He spent considerable time in New York, picking

up diplomas as well as tricks of the trade in a place considered the

ideal learning ground for those interested in fashion. |

|

Ismail also spent eight valuable weeks at Rampage and though the American

design house had taken him on as a merchandising intern, he ended

up designing their 2005 summer collection. Back in Pakistan, he then

launched his own label, designing smart western wear for the youth

of Karachi.

"Where most menswear designers in the country are catering to

the traditional market - mehndis and weddings being their peak season

- my business picks up when Grammarians and other young kids in Clifton

and Defence are having a farewell party or need to dress up for a

party or ball," he says. His clientele is molding his label,

he adds, and since these youngsters occasionally want to indulge in

eastern-contemporary clothing, he's branching off. And what about

designing for women?

"I don't intend getting into that," he says. "Every

third door you knock at in Pakistan will open to a woman who claims

she designs clothes. It's just not inspiring. Menswear, I feel is

a bigger challenge."

But isn't designing for women more lucrative as a business?

"I don't equate what I design with how much money I'll make on

a collection," he replies. "I want to keep my prices low

so my clients can afford what I make. It's never been about money

and always about what inspires me and what I enjoy. But being a business

student, I understand the mechanics of running a business, don't get

me wrong. We're all here to make money, only it doesn't have to be

the biggest reason for being in this business."

His criterion in the right place, Ismail Farid certainly is a fashion

designer to be taken seriously. His strength is his pursuit for perfectionism

and he takes pains for that, even if it means spending sleepless nights

in search of the perfect 'kashkol' (beggar's bowl) for a fashion shoot.

"We couldn't buy one off any beggar, though we offered as much

as 6000 rupees to one. Evidently these begging bowls are blessed upon

in Sehwan Sharif and then given to faqirs. They refuse to sell them

and we literally had to pawn one off a woman and return it to her

after the shoot was done."

As with finding the bowl, Ismail Farid is taking the road less traveled

towards success and yet he's confident it will find him. With what

he has to offer, it certainly will. Refering to this shoot and the

props he has used in it, Ismail believes things stand out when they

are placed in the unconventional place. Well, creating the avant garde

image is what fashion is all about and just living by that rule makes

Ismail Farid another delightfully eclectic addition to the next generation

of talented fashion designers.

– Photos by Rizwan-ul-Haq

|

| |

|