Editorial

Imbalance of power

To an outsider this may look surreal.

The fact that Osama Bin Laden’s presence in a garrison city did not bother

the people of this country at all but the breach of its sovereignty did. The

self-destructing content of the speeches delivered in a Jamaatud Dawah-sponsored

rally — the calls for Jihad and the vitriol against the US and India —

in Lahore would baffle him equally. And, finally, a casual reading of the

events surrounding a controversial memorandum and the response of various

institutions may make him want to bang his head against the wall.

military

Where the ‘rethink’ came

to an abrupt end

By deciding to file a response which is

separate from that of the federation, the military has put itself in a

quandary

By Farah Zia

The cat is out of the bag like never before. It may refuse to go back in

again and, to this extent, there is some room for hope — that the

imbalance of power might see a decisive shift to whichever side weighs

heavier.

judiciary

Necessity of

the doctrine

Every Martial Law in our country has been

followed by a PCO

By Shahzada Irfan Ahmed

The other day Prime Minister Yousaf Raza Gilani categorically stated

that the army and the judiciary were supporters of democracy and did not

have any intentions of derailing the democratic process in the country.

These words came in response to journalists’ questions about what they

called strained ties between the PPP government on the one side and the

judiciary and the military on the other.

two sides

History has it...

The democratic and liberal

Greek worldview versus the military mindset of the Spartans

By Sarwat Ali

In the ancient world, two views evolved over time that determined the

nature of the state and the society. These two views were dramatically

brought to the surface during the Peloponnesian Wars between the Greek City

states of Athens and Sparta around 500 BCE.

political

parties

Is the party over?

Pakistan’s political forces

have walked every time into a trap where they paradoxically end up being

manipulated into strengthening the Establishment and its agenda

By Adnan Rehmat

Political parties are vehicles for a state’s subjects to drive in and

arrive at a destination — usually imagined as the proverbial rainbow’s

end itself — that is determined in advance and one where they would all

like to go. But in a polity like Pakistan’s that is fractious, a country

that is a pluralist entity

media

The manipulator

is manipulated

Undermining the legitimacy of

parliamentary democracy has come naturally to the ‘people’s media’

By Adnan Rehmat

Reporting politics is as old a profession as politics. That’s pretty

straightforward. However, when it comes to Pakistan, how old really is

reporting about the national polity’s dominance of the Establishment? The

answer is not as straightforward as one would imagine.

religious

groups

Under ‘one’ umbrella

Islamists and jihadists pose

the biggest existentialist threat to the Pakistan military today

By Arif Jamal

The so-called Difa e Pakistan rally in Lahore on December18 sent shock

waves among Pakistan’s democratic forces. Ostensibly organised by the Difa

e Pakistan Council, a group of 40-odd Islamist-jihadist groups, the rally

was actually a show of force by the Jamatud Dawah (JuD).

Jinnah’s vision of Pakistan

By Prof Sharif al Mujahid

Jinnah was not a mere political leader, but also a statesman. Indeed his statesmanship streak influenced and determined his political leadership role increasingly as he negotiated the tortuous road to Pakistan in the 1940s.

From Jinnah to Quaid-i-Azam

By Nabiha Gul

It was close to the end of the 19th century and the world was experiencing several political upheavals when the struggle for independence from British Raj gained momentum in the subcontinent. Among other leaders, Muhammad Ali Jinnah vigorously advocated the rights of the people of the subcontinent and four decades later he became the founder of Pakistan?the Quaid-i-Azam. Hailing from a rich mercantile family, Muhammad Ali Jinnah was one of the eight children to Jinnah Bhai Poonja (Poonja Jinnah). There are multiple factors that influenced Muhammad Ali Jinnah’s political upbringing. It was only when he went to England for higher studies that he became familiar to Western ideas of liberalism and gradually spreading movements on the basis of nationalism. He also had an opportunity to closely observe the changing political and social scenarios in Europe based on democratic values.

Jinnah’s Pakistan: an integrated nation

By Muttahir Ahmed Khan

Truly speaking, if Quaid-i-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah had been present amongst us today he would have been extremely grief-stricken to see his nation falling prey to the fatal diseases of disunity, disharmony and disintegration. The whole voyage of the great leader’s struggle for a separate homeland for the Muslims of the subcontinent was based on the pivot of Muslim unity and oneness as a nation, without any thought of ethnic, lingual or sectarian discrimination. Addressing a public meeting at Dacca on March 21, 1948, Mr Jinnah clearly warned: “Let me warn you in the clearest terms of the dangers that still face Pakistan. Having failed to prevent the establishment of Pakistan and thwarted and frustrated by their failure, the enemies of Pakistan have now turned their attention to disrupt the State by creating a split amongst the Muslims of Pakistan. These attempts have taken the shape principally of encouraging provincialism. As long as you do not throw off this poison (of provincialism) from our body politic, you will never be able to weld yourself, mould yourself, galvanise yourself into a real, true nation. What we want is not to talk about Bengali, Punjabi, Sindhi, Baluchi, Pathan and so on. They are, of course, units. But I ask you: have you forgotten the lesson that was taught to us thirteen hundred years ago? If I may point out, you are all outsiders here. Who were the original inhabitants of Bengal? Not those who are now living here. So what is the use of saying, ‘We are Bengalis or Sindhis or Pathans or Punjabis.’ No, we are Muslims.”

QUAID-I-AZAM AS GOVERNOR GENERAL OF PAKISTAN

Dr M Yakub Mughul

The Quaid-i-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah was one of the greatest leaders of the modern age. He not only led his people to independence but founded a separate homeland, where they could mould their lives in accordance with the traditions of Islam and cultivate their culture and civilisation. This was a far greater achievement of the Quaid than any other national liberation leader. Other leaders struggled for independence within states already in existence whereas the Quaid alone sought a separate homeland where none had existed. This he achieved almost single-handedly and constitutionally and in the teeth of opposition.

Pakistan’s emergence was not just the emergence of a new State. It was created on the basis of Islamic ideology. Had Pakistan not been created, the Muslims would have been under the subjugation of militant Hindu majority in the united India and would have lost their identity in the Hindu majority.

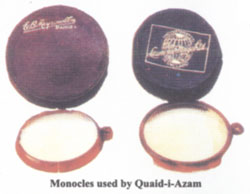

Quaid-i-Azam house museum

The softer side

By Uzma Batool

While crossing Shahrah-e- Faisal and Fatima Jinnah road, one comes across a strikingly elegant yellow/red stone building in the middle of a vast open piece of land which is popularly known as Flag Staff House or Quaid-i-Azam museum. This flag staff house belongs to father of the nation Quaid-i-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah.

Quaid through the years

1876: Mohammad Ali Jinnah was born on December 25, 1876.

1882: At the age of six he started learning Gugrati at home and got elementary education in primary school.

Editorial

Imbalance of power

To an outsider this may

look surreal. The fact that Osama Bin Laden’s presence in a garrison city

did not bother the people of this country at all but the breach of its

sovereignty did. The self-destructing content of the speeches delivered in a

Jamaatud Dawah-sponsored rally — the calls for Jihad and the vitriol

against the US and India — in Lahore would baffle him equally. And,

finally, a casual reading of the events surrounding a controversial

memorandum and the response of various institutions may make him want to

bang his head against the wall.

Call them inanities, plain

stupidities or vested interests at work, the sheer frequency of these

blunders is testing the patience of even a resilie nt

Pakistani. Enough of Sheikh Rasheed on television, they seem to be saying as

they wonder at the sudden birth of a ‘Civil Society Front’ out of

nowhere.

nt

Pakistani. Enough of Sheikh Rasheed on television, they seem to be saying as

they wonder at the sudden birth of a ‘Civil Society Front’ out of

nowhere.

As the drama enacts in the

Supreme Court with a volley of affidavits and counter-affidavits exchanged

on a daily basis, TNS seeks to look at the whole affair in the framework of

institutions and what we made of them. This, we feel, is a potentially

decisive moment in our history. The so-called Memogate offers a microcosmic

opportunity to see where our institutions stand today.

Whatever the short-term

effects of Memogate may be, through it we see the overarching influence of

one institution and how it used and dwarfed and inhibited the growth of

other institutions. Once the institutional imbalance was accepted, these

institutions overstepped their limits for obvious reasons. The institutions

which were permanently affected in this civil-military imbalance, and the

ones we have discussed in this Special Report, are political parties,

judiciary, media and religious groups apart from the military, of course.

But the original sin must

lie at the doorstep of this one institution. Ironically, the Memogate

scandal has served to reinforce this sense.

military

Where the ‘rethink’ came

to an abrupt end

By deciding to file a response

which is separate from that of the federation, the military has put itself

in a quandary

By Farah Zia

The cat is out of the bag

like never before. It may refuse to go back in again and, to this extent,

there is some room for hope — that the imbalance of power might see a

decisive shift to whichever side weighs heavier.

This time, it has come in

the shape of a memorandum delivered to Admiral Mike Mullen on the 10th of

May, 2011, the then chairman US joint chief of staff and revealed to the

Pakistani public in varying bits and pieces. The contents of the memo

reflect the aspirations of the civilian government in shaping a polity that

is at odds with the one desired by the country’s security establishment.

The consequences are for everyone to see.

The point is that in the

media-generated frenzy, headlines hog all attention. The details either get

lost or the wrong details are brought up for scrutiny. This unfortunately

happened with the said memo. Beyond the loud cries that lambast inviting a

foreign country to interfere in our local affairs, and despite the slack

language used by Mansoor Ijaz, the six points made in the memorandum clearly

spell out the grey areas of our foreign policy which is essentially

controlled by the military.

Speaking from the

standpoint of civilian supremacy, there is nothing wrong with any of these

six points (which are easy to Google if you missed them when they originally

came to light). The military, for obvious reasons, views it differently and

seems unprepared to give up the powers it feels belongs to itself. And,

hence, the separate affidavits submitted before the Supreme Court to show

that it stands apart from — and above — the elected government.

But is this the first time

that the military took a different stand? Certainly not. It always spoke

from a position of strength and managed to have its way.

The assassination of

Benazir Bhutto drew a different kind of response in the initial months,

though. Before the election of 2008, in January, General Ashfaq Parvez

Kayani “passed a directive which ordered military officers not to maintain

contacts with politicians.” On February 13, 2008, he ordered the

withdrawal of military officers from all of Pakistan’s government civil

departments (the details about the implementation never got public).

After the elections, on

March 7, 2008, he “confirmed that Pakistan’s armed forces will stay out

of politics and support the new government.” Speaking to a gathering of

military commanders in Rawalpindi, he said that “the army fully stands

behind the democratic process and is committed to playing its constitutional

role.”

That is where the

‘rethink’ came to an abrupt end. Curse the elected government for

getting the wrong signals. Curse Prime Minister Gilani for deciding to put

the ISI under the control of the Ministry of Interior (he was made to

de-notify the order within hours) and curse him for announcing to send the

DG ISI to India for a joint investigation of Mumbai attacks (the DG did not

go). Both the incidents came rather early on, in 2008, and the government

was expected to have learnt its lesson for good.

For most part, it did.

If, however, the occasion

required, the corps commanders would sit as a parallel cabinet and announce

their displeasure over, say, the conditionalities of Kerry Lugar Bill. On

the other hand, if silence was the need of the hour, like in the case of

release of Raymond Davis or during most drone strikes, it was duly

maintained.

Meanwhile, the power

equation (read the status quo) sustained as the mantra of all institutions

“on the same page” was repeated ad nauseam. If the Newsweek named

General Ashfaq Parvez Kayani the 20th most powerful person in the world in

2008, the Forbes magazine declared him the 34th most powerful person in

2011. Not to forget that in July 2010 the prime minister extended Kayani’s

term as Chief of the Army Staff by three years, making him the first

four-star general to receive a term extension from any democratic

government.

But then came May 2011 or,

to borrow from Mansoor Ijaz (and, by implication, Husain Haqqani), the

“1971 moment”. Once again the state is doing what it did post-1971.

As one of the country’s

leading political parties PML-N decided to take the case for inquiry away

from its rightful domain, the parliament, into the Supreme Court, the COAS

and the DG ISI decided to file separate affidavits.

The truth is that by doing

so, the military has put itself in a quandary. The existence of the memo

itself has proved that it stands on a shaky ground, and by coming out in the

open it must prove, to itself more than anyone else, that it has regained

its feet. But that’s not where the matter ends. All eyes of the world are

set on the ‘Memogate’ inquiry — to see what steps does the military

take vis-a-vis the elected civilian dispensation. Whether it is ready to

wind up the current experiment and take overt charge of the country or

whether it would continue to operate from behind the scenes (Bangladesh and

Burma models are not just thrown up for discussion’s sake).

Opinion is divided on what

course the military would take. Even if the international dimension is kept

aside for the moment, military’s direct rule is rejected for the simple

reason that this will put the integrity of the country at stake, given the

insurgency in Balochistan and the expected unease in Sindh. Does this mean

that the security establishment now reels under its own weight?

The quandary holds even if

the security establishment decides to bring in any other political

dispensation, in whatever form (the Bangladesh model failed eventually while

the Burma model is untenable given our peculiar experience with terrorism).

This new political dispensation, we fear, shall bring in its own memo-like

blueprint, not addressed to a US official maybe but drawn along similar

lines as this one.

This is the lesson of

history and the structural flaw that Pakistan must live with — looks like

the Memogate is going to rub the Pakistani institutions the wrong way.

judiciary

Necessity of

the doctrine

Every Martial Law in our country has been followed by a PCO

By Shahzada Irfan Ahmed

The other day Prime

Minister Yousaf Raza Gilani categorically stated that the army and the

judiciary were supporters of democracy and did not have any intentions of

derailing the democratic process in the country. These words came in

response to journalists’ questions about what they called strained ties

between the PPP government on the one side and the judiciary and the

military on the other.

Amid speculations that

change in government, if any, would come through a court order and that the

military would be there to help execute it, this statement was termed a

feeble attempt to diffuse the tensions existing among state institutions.

No doubt, the PM’s

statement was expected and media concerns genuine keeping in view the

history of the country. Many a time in the past elected governments were

sent home on different charges by the military and the sitting judiciary had

approved these acts. The latter showed defiance as well but such instances

were very few and it’s a comparatively newer phenomenon in the history of

military-judiciary relations.

A look into the annals of

history shows how the removal of the Khawaja Nazimuddin government by

Governor-General Ghulam Muhammad in 1954 was approved by the judiciary under

the “Doctrine of Necessity.” The term used for the first time in

Pakistan by Chief Justice Munir, while hearing a petition filed by Maulvi

Tamizuddin, president of the dissolved constituent assembly, was frequently

referred to by the judiciary in years to follow to give approval to military

coups.

Used to describe the basis

on which extra-legal actions by state actors, which are designed to restore

order, are declared legal, the term (“Doctrine of Necessity”) formed the

basis of the martial laws of General Ayub Khan and General Yahya Khan in

1958 and 1969 respectively. The superior judiciary this way gave a legal

cover to these acts at the cost of democratically elected governments.

Whether they qualified to continue to be in power was a totally different

question.

The first two military

rulers abrogated the constitution with impunity as Article 6 was

incorporated in the constitution only in 1973. Under this article, acts such

as abrogation of constitution by force were declared acts of high treason.

It is believed that for this very reason, Gen Ziaul Haq suspended the

constitution in 1977 and stayed away from abrogating it.

Unfortunately, the

justification for Zia’s martial law was once again the same doctrine of

necessity. Ironically, the person who got this article inducted in the

constitution to stop the way of a military dictator was awarded death

sentence and all appeals against the decision were rejected by the

judiciary.

Musharraf’s 1998 coup

was taken a bit differently by the judiciary and its approval was subjected

to the condition of his holding general elections within three years.

The rare confrontation

between the military and the judiciary also had its manifestation during

Musharraf’s tenure when Chief Justice Iftikhar Chaudhry refused to resign

on his demand on March 3, 2007. In November the same year, 60 judges

followed him after the imposition of emergency in the country as they all

stood deposed.

It’s an established fact

that even when the army is not in power, its political muscle has been

present. The army has even established military courts, a move which was

challenged by former Chief Justice Sajjad Ali Shah which in his opinion was

an attempt to set up a parallel judicial system.

The military rules have

always won legitimacy from the succeeding elected assemblies whose first

acts have been to indemnify the acts of their predecessors. For example,

Musharraf’s Legal Framework Order (LFO) legitimised his tenure which,

according to him, enjoyed full support of the judiciary.

“I don’t need the

assemblies’ approval. If anyone has an objection to this, he’d better go

to the Supreme Court which has mandated us to amend the constitution,” was

what he said on the occasion.

Coming back to the current

fiasco over Memogate, the general perception is that this time the coup, if

any, would be a judicial one. The court many think may give an order against

the government and none other than the army will be asked to execute it.

This would not be

unconstitutional as the apex court can call the Army for help in getting its

verdict implemented under Article 190 of the Constitution of Pakistan. The

apex court has given many decisions against the sitting government but these

could not be executed. The next, if given against the government and in

favour of the military, may not lack the enforcement power lacking so far.

two

sides

History has it...

The democratic and liberal Greek worldview versus the military mindset of

the Spartans

By Sarwat Ali

In the ancient world, two

views evolved over time that determined the nature of the state and the

society. These two views were dramatically brought to the surface during the

Peloponnesian Wars between the Greek City states of Athens and Sparta around

500 BCE.

The Spartans were great

warriors and laid huge premium on building the military might of their

state. They premised that the defence of the city state, the highest virtue

that could be attained was only possible by investing hugely in their

military infrastructure.

The most important aspect

of any state are the people — Sparta invested heavily in the citizens

which revolved round their education and training totally focused on the

ability to be great soldiers. Education primarily was meant to train the

young in the art of warfare and to be militaristically ready to defend the

city state. This made all other institutions dovetail to this ideal. The

youth were made to give preference to the art of warfare and the entire

system was conditioned by it. The society, too, was structured in such a way

that the ideal of war was upheld and guarded with full devotion and

reverence. All men had to be militaristically trained and to be a soldier

was the most prized status and station in the society. They espoused

oligarchy, abhorred democracy and insisted on building a society that was

focused, regimented and geared towards singular objective. All else was

either wasteful or mere indulgence which the human and material resources of

the city state could hardly afford.

Laconophilia, the love or

admiration of Sparta and of the Spartan culture or constitution, typically

means praise, valour and success in war, laconic austerity and

self-restraint, aristocratic and virtuous ways, the stable order of

political life and constitution. Spartan state was seen as ideal theory

realised in practice and was admired not for its art and literature, but for

the disciplined character of its citizens. The Lacedemonians were masters

not of creating things in words or stone but of men.

On the other hand, their

opponents — the Athenians — espoused a different world view. The

Poleponnesian Wars were as much a battle of two city states as of two world

views. The Greek were basically democrats and took great pride in building a

society that was based on the freedom of ideas and thinking, the resultant

expression of that endeavour, philosophy and arts were highly-prized. The

military mindset was ensconced in the bigger picture of what they wanted

their society to be, more wholesome and open, not enslaved by one

overwhelming mission, the defence of their city-state.

Stressing on the

speculative aspects of thought, the human beings were perceived as deserving

of a higher purpose and to be creative. They produced philosophers,

political scientists, artists; created epics and tragedies and guaranteed

space for those not that purpose-driven.

There were philosophers

who just thought and whiled away their time in sophistry, poets who wrote

and wallowed in the luxury of their imagination, builders who placed form

above content in seeking the ultimate design that may have escaped the

building on the truth of received wisdom.

The infiniteness of reason

and the compactness of imagination were cherished; “shauq e fazool” was

valued as more things in heaven and earth than could be dreamt of in a

philosophy were pursued. For them human beings were more important as they

created society and not the state that created its citizens.

Athenian society thrived

in diversity and a work ethic that was not based on regimentation — the

idea of discipline more subjective than overt, and the ideality and idleness

not that grave crimes.

Similarly, criticism and

cynicism was entertained as human activities not totally wasteful, and even

if they were, so what. The task of a goal-oriented order was relegated in

pursuit of discovering a goal.

political

parties

Is the party over?

Pakistan’s political forces have walked every time into a trap where

they paradoxically end up being manipulated into strengthening the

Establishment and its agenda

By Adnan Rehmat

Political parties are

vehicles for a state’s subjects to drive in and arrive at a destination

— usually imagined as the proverbial rainbow’s end itself — that is

determined in advance and one where they would all like to go. But in a

polity like Pakistan’s that is fractious, a country that is a pluralist

entity but pretends to be a singularity and boasts a critical mass of

citizens that is deprived of even the fundamental guarantees that a written

constitution promises — political parties have fallen short of

expectations when it comes to delivering them to their destination.

True, the conditions that

some of the political parties that are openly owned up by many millions in

the country have navigated have been darned difficult and their job made

thorny by the real overlords of Pakistan. They have fought valiant battles

that were not even supposed to exist in the first place since the

Constitution promises them not just legitimacy but necessity and

inevitability even. However, the bottomline is that national dreams and

aspirations have soured and the disillusionment with political parties of

Pakistan — whether they are the mainstream Big Two or the provincial

powerhouses — is setting in deep.

Or, is it? What about all

the heads Imran Khan is turning and the headlines his Tehrik-e-Insaf is

running away with, leaving even established political parties nervous in

their shoes ahead of the race for the hustings? Are all these the signs of a

political transition where the hopes of tens of millions of a relatively new

generation of Pakistanis are growing weary of the old ways of politics, when

a majority outsourced protection of their interests to political parties, in

a new age of greater individual liberty and growing impatience?

The major political

parties are certainly about to find out. Yes, some important fingers are

pointing towards the Establishment as the patrons of the newest kid on

Pakistan’s political block. But every firmly established political party

with the ability to win votes by the millions, be they kings or kingmakers

at the national or provincial level with at least 15 years behind them —

Pakistan People’s Party, Pakistan Muslim League-N, Awami National Party

and Muttahida Qaumi Movement — are not really asking the right questions

in-house or out in the public.

If Imran Khan and his

party are being given more than just a quiet backing by the Establishment,

why is PPP ready to be manipulated into believing that the ‘Captain’ can

only harm its principal rival PML-N? By tactical level politics of

indirectly supporting PTI against an admittedly pesky PML-N isn’t PPP

undermining its own interest of promoting a largely two-party system that

nurtures within it the surest guarantee of political longevity for itself?

By focusing on personalities — read: Asif Zardari — rather than the

government’s unravelling economic and social policies, isn’t Nawaz

Sharif and his aides only helping themselves to be manipulated once again by

the military into discrediting the very structural edifice upon which the

political legitimacy of the transition from Musharraf’s ham-fisted

military reign to constitutional, representative government has been built,

which includes their Punjab government?

That Pakistan’s biggest

political fights are not played out in the streets and homes among political

parties in the legitimate battle for people’s mandate but behind closed

doors between the constitutional political forces and the illegitimate

Establishment and their cohorts for the control of the country is hardly a

secret. In fact, the current phase of this long-running battle between these

two protagonists is being played out in the highest court of the land,

turning it from a tragedy to a farce. Where this heartless battle is headed

can be understood by the fact that the military has now formally given up

even a pretence that it is supposed to be a part of the government.

This then brings us to the

old question: For the control of Pakistan — and, by that extension, to the

destiny and destination of 180m Pakistanis — who is manipulating who? For

even an average 23 year old Pakistani it’s obvious that against its old

foe PPP, the military is manipulating PML-N and PTI. By way of promise, the

spoils for this include a chance at forming the next government in

Islamabad. The PPP is being manipulated by the military into thinking it can

manipulate PTI into cutting into PML-N’s house in Punjab. The PTI is, of

course, happy to be manipulated into a position where it can take on

Pakistan’s oldest political foes (two wickets with one ball).

A departure from their own

stated objectives and people’s mandates, Pakistan’s political forces

have walked every time into a trap where they paradoxically end up being

manipulated into strengthening the Establishment and its agenda of a

stranglehold over the state’s resources, taking the country in a direction

opposite to what they started out for in 1947.

Who did PPP strengthen by

launching a nuclear programme; appeasing Islamic forces (declaring a section

of the population “kafirs” by law, Friday as weekend, banning alcohol,

etc.); creating ISI and giving it a political role; increasing the military

budget threefold even after it lost East Pakistan; cutting a deal with the

military duo of Musharraf and Kayani in the shape of the NRO; and,

unforgivably, giving a face-saving to the military after Osama Bin Laden was

found in Pakistan under its nose?

Who did PML-N strengthen

by testing nuclear, dealing with an army chief to spare its leaders a stint

in prison; taking PPP to court on Memogate and, therefore, giving legitimacy

to the Establishment’s re-establishment of its old game of de-legitimising

political forces; siding with the judges and giving them the right to

undermine elected governments who restored them rather than take on generals

who are still in office who were among those who forced the chief justice

out and jailed his fellow judges; and by not sending Nawaz Sharif to the

current parliament and strengthening it?

The thing is that the

morality of political parties has to grow out of the conscience and the

participation of the voters, but by letting themselves be manipulated by the

Establishment again and again, they are ending up not just becoming under-legitimised

but also taking the people to a destination they did not pay for.

media

The manipulator

is manipulated

Undermining the legitimacy of parliamentary democracy has come naturally

to the ‘people’s media’

By Adnan Rehmat

Reporting politics is as

old a profession as politics. That’s pretty straightforward. However, when

it comes to Pakistan, how old really is reporting about the national

polity’s dominance of the Establishment? The answer is not as

straightforward as one would imagine.

Consider: until only a

decade ago, there was no independent TV or television news in Pakistan,

which means that only the state-owned PTV was the primary source of formal

information as a default. Even as recently as five years ago, there were

barely five TV channels in the private sector, which offered any decent news

worth its name or real-time information. Now it’s a tsunami, to use the

favourite word of Imran Khan, who is the Pakistani media’s idea of a

politician and leader, currently.

Until the independent

broadcast media came along some years ago, the state media controlled even

by the elected governments could not dare offer open opinion that went

against the self-assumed extra-constitutional role of arbitrating national

destiny by the military Establishment. There never has been uttered the

“T” word — treason — on the state media, either under elected or

military governments, when it comes to the actions of a few generals who did

what is unthinkable in democracies. This despite the fact that there have

been three coups d etat in Pakistan where the army chiefs violated the

constitution and overthrew elected governments. All of them either died or

were discharged with state honours.

No national honours for

the elected leaders, however. The state media, including PTV and Radio

Pakistan — under Generals Zia and Musharraf — have openly painted the

country’s first elected prime minister as a “traitor” who allegedly

broke up the country (even though General Yahya, yet another army chief, was

the ruler!) and hung him, elected prime minister Benazir Bhutto as a

“security risk” and elected prime minister Nawaz Sharif as a

“hijacker”, dismissing their governments with contempt.

Which is why high hopes

have rested on independent broadcast media — supposedly the voice of the

people and the guardian of their democratic interest. Because only about 15m

Pakistanis get their information from newspapers and a very large majority

of the country’s 180m citizens from TV media, it is crucial that this

medium understands and acts out on its principal responsibility as a

watchdog of not the Establishment’s interests but the guardian of public

interest.

But, is it? With the

exception of the summer of 2007, when Musharraf’s fit of soldierly impulse

against a Supreme Court packed with his cronies made heroes out of them from

the stand in support of the constitution taken by the media, Pakistan’s

independent TV has in a big part turned out to be not the educator on and

articulator of the real big fight for the people’s destiny as a pluralist

democracy that is played out behind the scenes. Accountability of the

government — another central role of the media — is one thing but

actually taking positions that undermine the legitimacy of parliamentary

democracy has come astonishingly naturally to the supposedly ‘people’s

media’ of the new millennium in Pakistan.

There have been at least

three instances in 2011 alone that have established that the independent TV

media in Pakistan have failed in their role of either informing or educating

the people and on what really is happening when the people were primed to

make up their minds on the issue about who really governs the country. The

first was when CIA agent Raymond Davies was caught in Lahore, the second

when Osama Bin Laden was found comfortably snuggled in Abbottabad and the

third when Nato troops gunned down Pakistani soldiers on the Afghan border.

In each of these three

instances, the media was manipulated by the military Establishment into

taking anti-American sentiments sky high to increase their leverage over

Washington. By using the Establishment’s standard narrative of

nationalism, religion and patriotism, the media got played into ignoring the

basic principles of journalism that demand a professional, neutral posture

based on fact rather than opinion. TV in Pakistan is full of opinion-making

anchorpersons on primetime talk shows that are always blurring the line

between fact and opinion and the line between opinion and analysis.

For any media

professional, in its short life of a few years, the prime medium of

public’s information in Pakistan has proved an embarrassing advocate of

the cliché and the stereotype. “Parliament has failed,” (really? Who

has cleansed the constitution of a large part of the legacies of Generals

Zia and Musharraf, passed a battery of pro-women laws and got back powers

from the president that didn’t belong to him?) “Military is the guardian

of national frontiers,” (as if the military is not part of the government

and the government and parliament are not the guardians). “The government

is corrupt,” (which court has declared the government corrupt?) “Doing

business secretly with the US is against the national interest,” (So, if a

military government does it, it’s in national interest?)

The media in Pakistan in

general has been easily manipulated, with the exception of print media in

the past, by the Establishment but what is happening now is that the TV

media is openly and unthinkingly strengthening the military establishment

and the judiciary against the parliament, which means the media is becoming

part of the story and of the manipulation — a political actor itself. How

professional is this? The answer is obvious to all, except to the

media.

religious

groups

Under ‘one’ umbrella

Islamists and jihadists pose the biggest existentialist threat to the

Pakistan military today

By Arif Jamal

The so-called Difa e

Pakistan rally in Lahore on December18 sent shock waves among Pakistan’s

democratic forces. Ostensibly organised by the Difa e Pakistan Council, a

group of 40-odd Islamist-jihadist groups, the rally was actually a show of

force by the Jamatud Dawah (JuD).

The rally comes at a time

when the general elections are a little more than a year away if the

political system is not derailed once again. Some of the analysts and

commentators in the Pakistani media see it as an attempt by the Deep State

to gather its ‘client’ political/religious groups under one umbrella to

defeat the democratic forces. They see it as an attempt to create an

alliance on the lines of the IJI or the MMA.

The fear may be misplaced

as the JuD is not likely to take part in any electoral activity in the near

future. However, the rally is significant as it is for the first time that

the JuD has organised such a big political rally, even though it has held

far bigger religious rallies in the past.

The cause of unease about

the intentions of the Deep State is the fact that the alliance between the

Deep State and the religious parties has become so deep. It is quite natural

that the rally has once again brought the subject of the military-mullah

alliance to the fore. It has strengthened the suspicions that the Deep State

is once again waiting in the wings to use its client religious/political

parties to manipulate the results of the next general elections. Rallies

such as the Difa-e-Pakistan may strengthen the pro-military political forces

as the general election nears; the contents of the speeches make it clear

that the rally aims at paving the way for the fuller use of jihad as an

instrument of policy by the Deep State in the emerging regional scene.

The mullah-military

alliance was forged during the Bangladesh war of independence when the

Jamaat-i-Islami of Pakistan formed al-Badr and al-Shams to fight alongside

the Pakistan Army against the Bengali nationalists in the erstwhile East

Pakistan. Al-Badr and al-Shams fought alongside the Pakistan army and

brutally targeted and killed the Bengali intelligentsia. They lost the war

but they understood the importance of alliance between the army and the

religious parties. The Pakistani military and religious parties have been

inseparable since then. The trend started by the Jamaat-i-Islami of Pakistan

was later followed by all other religious parties.

The alliance bore fruit

for both sides in 1977 when the military dismissed the

democratically-elected government of Z.A. Bhutto as a result of a prolonged

agitation by the religious parties. Neither of them could have brought the

Bhutto government down alone. For the first time, they shared power. The

significant thing about the 1977 coup was that it made it clear that the

Pakistani military was no more a secular force. The military regime under

General Ziaul Haq would not have survived without the support from the

religious parties such as the Jamaat-i-Islami, Jamiat-i-Ulema-i-Pakistan and

Jamiat-i-Ulema-i-Islam (Samiul Haq). At the same time, these parties could

not have grown in strength and numbers in a democratic political system. To

create a support base and survive in power, Gen. Ziaul Haq encouraged

sectarian and jihadist groups such as Sipah-e-Sahaba Pakistan.

The jihad in Afghanistan

and, later, in Kashmir not only strengthened the Islamist parties in an

unprecedented way but also turned them violent. Jihadist groups mushroomed

and most religious parties formed their armed wings. The military regime

used jihad as an instrument of defence policy. The jihadist groups were

doing both in Afghanistan and India what the military could not do openly.

On the one hand, they bled the Soviets in Afghanistan and, on the other

hand, they tried (unsuccessfully) to cause the death of India by using the

tactic of thousands cuts. The military ignored the high cost for the

temporary successes. The strategy of using jihad as an instrument of defence

policy proved the best policy as it involved virtually no loss of Pakistani

soldiers’ lives. Consequently, they provided unlimited resources to

jihadist groups.

After the success of the

Pakistan National Alliance (PNA), an opposition alliance dominated by

religious parties, the Islamist parties were also used to destabilise the

democratically-elected governments in the 1990s. Before each illegal

dismissal of a democratic government, the Islamist/jihadist groups brought

in a wave of violence. The military created Islamic Jamhoori Ittehad (IJI)

in the late 1980s to defeat the PPP. In early 2000s, the military encouraged

the formation of Muttahidda Majlis-e-Amal (MMA), commonly known as the

mullah-military alliance. In the deeply manipulated elections in 2002, the

MMA emerged as a major political player. It formed government in the former

NWFP and joined the coalition in Balochistan. In the centre, it played the

friendly opposition, facilitating General Musharraf’s rule.

On the face of it, the

military has been successfully using the Islamist/jihadist parties to

further its agenda. However, the rise of Islamist/jihadist parties proved to

be a double-edged sword for their benefactors and creators. On the one hand,

Islamist/jihadist parties gained in strength and numbers under the patronage

of the military and, on the other hand, they ideologically influenced the

military. Consequently, when the jihadi Frankenstein turned against the

military in the wake of the US-led invasion of Afghanistan in 2001, they got

support from within the military.

Today, the Islamists and

jihadists pose the biggest existential threat to the Pakistani military but

their influence within the military is such that the military is unable to

abandon the use of jihad as an instrument of defence policy.

The

writer is a US-based journalist and author of Shadow War – The Untold

Story of Jihad in Kashmir

JInnah’s vision of Pakistan

By Prof Sharif al Mujahid

Jinnah was not a mere political leader, but also a statesman. Indeed his statesmanship streak influenced and determined his political leadership role increasingly as he negotiated the tortuous road to Pakistan in the 1940s.

increasingly as he negotiated the tortuous road to Pakistan in the 1940s.

A statesman looks at problems and developments on a long-term basis unlike a politician who deals with matters of the moment with short-term vision. This is not only in terms of immediate goals, but, more importantly how they could be fitted in and could be integrated within the long-term, larger perspective and more overriding goals.

Hence a statesman constantly and continuously tends to prognosticate and keep in view the long-term consequences of day-to-day developments he is confronted with. Above all, a statesman looks at events and problems through the prism of a grand vision.

No wonder, Jinnah had developed the demand for Pakistan with a vision. It is not merely that a Muslim homeland in the subcontinent had to be created, but also how it should be structured, what orientation it should opt for, and what ultimate goals it should pursue. All this meant to make its establishment, meaningful and significant to the masses in terms of their living standards, economic betterment, cultural uplift, and spiritual contentment.

Political independence from both the British rule and Hindu domination was, of course, the immediate goal, the short-hand metaphor, as it were. But what was to make it meaningful was a process of quests that would change the face of the Muslim homeland for a better tomorrow, a brave new world.

Quests for ideological resurgence, cultural renaissance, economic betterment and social welfare were main goals of this struggle. And this is precisely how Jinnah spelled out the rationale for the Pakistan demand in his epochal March 23, 1940, address in Lahore. He said, “... we wish our people to develop to the fullest our spiritual, cultural, economic, social and political life in a way that we think best and in consonance with our own ideals and according to the genius of the people”.

Thus, his numerous pronouncements from 1940 to 1948 provide guidelines in a full measure that, when taken together, portray his vision of Pakistan. First, in his August 11, 1947, address he called for an indivisible Pakistani nationhood, a concept by which all the inhabitants, no matter what their race, colour or religion would be citizens of Pakistan with equal rights, privileges and obligations.

Pakistan. First, in his August 11, 1947, address he called for an indivisible Pakistani nationhood, a concept by which all the inhabitants, no matter what their race, colour or religion would be citizens of Pakistan with equal rights, privileges and obligations.

Second, on February 21, 1948, he stressed the need for “the development and maintenance of Islamic democracy, Islamic social justice and equality of manhood”. Earlier, in his June 18, 1945, message to the Frontier Muslim Students Federation, he had talked of “the Muslim ideology which has (got to be preserved, which has come to us as a precious gift and treasure, and which, we hope, others will share”.

In his broadcast to the United States in February 1948, he was sure that the Pakistan’s constitution would be of “a democratic type, embodying the essential principles of Islam”. At the same time he reaffirmed unequivocally that “Pakistan is not going to be a theocratic state ... to be ruled by priests with a divine mission”. Thus, he stood for a democratic face of Islam - a pluralist face of Islam.

The Quaid stood not only against theocracy, but also against sectarianism. “Islam”, “he said does not recognise any kind of distinction of caste and the Prophet [PBUH] was able to level down all castes and created national unity among Arabs. Our bedrock and sheet-anchor is Islam. There is no question even of Shias and Sunnis. We are one and we must move as one nation, and then alone we shall be able to retain Pakistan”.

Unfortunately though, sectarianism has raised its ugly head in Pakistan during the last fifteen years, creating serious problems for Pakistan. Curbing religious extremism and marginalising jehadi and terrorist groups are indeed, among the most critical challenges confronting Pakistan today. The future face of Pakistan depends for the most part on how we go about tackling these critical problems.

Jinnah had invoked Islam because, as he had repeatedly said, “Islam and its idealism have taught us democracy. Islam has taught equality, justice and fairplay to everybody. What reason is there for anyone to fear democracy, equality, freedom on the highest standard of integrity and on the basis of fairplay and justice for everyday?

“.... Let us make it (the future constitution of Pakistan). We shall make it and we will show it to the world.”

At the political level, Jinnah stood for undiluted democracy, for constitutionalism, for autonomy of the three pillars of the state (executive, legislative and judiciary) and for a free press, for civil liberties and a civil society, for the rule of the law, for accountability, for a code of public morality. And it is in the formulation of such a code that Islamic principles would come in handy, and that ideology would play a pivotal role in Pakistan’s body politic, but, of course, with the consent of the general populace.

He stood for moderation, gradualism, constitutionalism and consensual politics all through his public life. He believed in building up a consensus on an issue, step by step. He believed that controversies should be resolved through debate, a discussion in the assembly chamber and not through violence in the streets. He believed in democracy and not monocracy.

He believed on the lines of Disraeli who laid down the axiomatic rules for the birth and maintenance of a stable and self-propelling democracy when he said, “We must educate our masters, the people; otherwise we would be at the mercy of a mob masquerading as democracy”. This is tragically what has been missing in Pakistan since the early 1950s. More often than not, most of our political leaders succumb to wild rhetoric, weakening the democratic temper of the masses and strengthening the trend towards monocracy or dictatorship.

On the economic side, Jinnah stood for a welfare state. Among others this would call for structural changes in the economy, ensuring a balanced and mixed economy with a more equitable distribution of wealth. He stood for full employment opportunities for one and all, for a contented labour, for a fair deal to the farmer, and for human resource development at all levels. Finally, his call for an Islamic economic system should not be misinterpreted with the riba question. It is essentially meant to ensure economic equity and social justice to one and all, without any discrimination whatsoever.

Jinnah stood for enforcing law and order, for the elimination of nepotism, bribery corruption and black marketing, for wiping out distinction of race, religion, colour and language, for providing equal opportunities to one and all and for the economic betterment of the masses. “Why would I turn my blood into water, run about and take so much trouble? Not for the capitalists surely, but for you, the poor people”, he pointedly told his audience at Calcutta on March 1, 1946.

He counseled the first Constituent Assembly on August 11, 1947. “Now, if we want to make this great State of Pakistan happy and prosperous we should wholly and solely concentrate on the well-being of the people, and especially of the masses and the poor”. He also stood for the emancipation of women for conceding them their due rights, and for taking them along with men side by side in all spheres of national life.

In short, he wanted Pakistan to be progressive, forward-looking, modern and welfare-orientated but firmly anchored to the pristine principles of Islam, since these principles are firmly rooted in the enduring traits of equality, solidarity, freedom and emancipation of the marginalised sections of society.

This, then, represents the Quaid’s vision of Pakistan. And unless and until we translate his guidelines into public policy and ground reality, Pakistan would not become the sort of Pakistan which the Quaid had envisioned.

- HEC Distinguished National Professor, the writer has recently co-edited Unesco’s History of Humanity, vol. VI, and The Jinnah Anthology (2010) and edited In Quest of Jinnah (2007), the only oral history on Pakistan’s founding father.

caption

The Quaid-i-Azam delivering his first address to the Constituent Assembly of Pakistan on August 11, 1947

caption

First Cabinet of Pakistan (from left): Fazlur Rehman, Ghulam Muhammad, Liaquat Ali Khan, M A Jinnah, I I Chundrigar, Abdul Rab Nishtar and Abdul Sattar Pirzada

“Few individuals significantly alter the course of history. Fewer still modify the map of the world. Hardly anyone can be credited with creating a Nation-State. Mohammad Ali Jinnah did all three. Hailed as a ‘Great Leader’ (Quaid-i-Azam) of Pakistan and its first Governor-General, Jinnah virtually conjured that country into statehood by the force of his indomitable will.”

- Stanley Wolpert

From Jinnah to Quaid-i-Azam

By Nabiha Gul

It was close to the end of the 19th century and the world was experiencing several political upheavals when the struggle for independence from British Raj gained momentum in the subcontinent. Among other leaders, Muhammad Ali Jinnah vigorously advocated the rights of the people of the subcontinent and four decades later he became the founder of Pakistan?the Quaid-i-Azam. Hailing from a rich mercantile family, Muhammad Ali Jinnah was one of the eight children to Jinnah Bhai Poonja (Poonja Jinnah). There are multiple factors that influenced Muhammad Ali Jinnah’s political upbringing. It was only when he went to England for higher studies that he became familiar to Western ideas of liberalism and gradually spreading movements on the basis of nationalism. He also had an opportunity to closely observe the changing political and social scenarios in Europe based on democratic values.

momentum in the subcontinent. Among other leaders, Muhammad Ali Jinnah vigorously advocated the rights of the people of the subcontinent and four decades later he became the founder of Pakistan?the Quaid-i-Azam. Hailing from a rich mercantile family, Muhammad Ali Jinnah was one of the eight children to Jinnah Bhai Poonja (Poonja Jinnah). There are multiple factors that influenced Muhammad Ali Jinnah’s political upbringing. It was only when he went to England for higher studies that he became familiar to Western ideas of liberalism and gradually spreading movements on the basis of nationalism. He also had an opportunity to closely observe the changing political and social scenarios in Europe based on democratic values.

Upon his return from England, Muhammad Ali Jinnah sensed the wave of change in the politics of the subcontinent where the independence movement had taken its roots. On his part, Muhammad Ali Jinnah had a clear political thought based on the ideals of democracy: equality, civil rights, minorities’ rights, representative government, independent judiciary, political reforms and women’s empowerment. He had begun advocating the rights of the people of the subcontinent by joining the Indian National Congress. He was a strong advocate of Hindu-Muslim unity. However, soon after realising that the agenda of the Congress clashed with his own political principles, he quit the Congress and joined the All India Muslim League. It was the platform of the Muslim League that drew the Muslims of the subcontinent together; especially there was a proactive participation of Muslim women in the movement for a separate independent land. An important aspect of Jinnah’s political thought was ‘nationalism’, and in case of the subcontinent, Muslims were recognised as one of the two nations, and All India Muslim League brought them together on the basis of commonality of the religion. For long, the Muslims in the subcontinent had been keeping their distinct identity and were seeking equal representation in political and social affairs in the region. Jinnah furthered the agenda of the Muslim intellectuals and political thinkers to secure equal rights for Muslims under the banner of the Muslim League.

Jinnah, then, expressed his political thought and vision for a future separate homeland for Muslims determinedly. On several occasions his words reflected his political vision as he always stood by his own political principles. On the historical occasion of March 23, 1940 he declared:

“Muslims are a nation by any definition. We wish our people the fullest spiritual, cultural, economic and political life in a way that we think best and in consonance with our own ideals and according to the genius of our people. It is quite clear that Hindus and Muslims derive their inspiration from different sources of history. They have different epics, different heroes and different episodes. Very often the hero of one is the foe of the other, and likewise, their victories and defeats overlap. To yoke together two such nations under a single state, one as a numerical minority and the other as a majority, must lead to growing discontent and final destruction of any fabric that may be so built up for the government of such a state.”

With his determination and resolve, Jinnah undisputedly became the great leader of the Muslims. Gradually, he was implanting the ideals of democracy into the Pakistan Movement as he stressed upon equal rights for all on many occasions and participation of Muslim women in the movement.

In his message on Pakistan Day, March 23, 1943, Jinnah stated:

“I particularly appeal to our intelligentsia and Muslim students to come forward and rise to the occasion. You have performed wonders in the past. You are still capable of repeating the history. You are not lacking in the great qualities and virtues in comparison with the other nations. Only you have to be fully conscious of that fact and to act with courage, faith and unity.”

It was Jinnah’s political vision that Muslim League had founded women’s wing to facilitate women’s participation in the Pakistan Movement. He believed in the empowerment of women and wanted them to work alongside men for the creation of a separate land. Addressing a gathering of students at the Islamia College for Women on March 25, 1940, Jinnah expressed his belief in the strength of women:

“I have always maintained that no nation can ever be worthy of its existence that cannot take its women along with men. No struggle can ever succeed without women participating side by side with men. There are two powers in the world; one is the sword and the other is the pen. There is a great competition and rivalry between the two. There is a third power stronger than both, that of the women.”

A careful analysis of Jinnah’s political career reveals that though his entry into politics was a matter of circumstances, he carried his political career with a purpose. From Muhammad Ali Jinnah he travelled through a difficult path and had a rough journey to become the Quaid-e-Azam. A firm believer of Unity, Faith, and Discipline, the Quaid-e-Azam left the nation with a thought provoking message:

“My message to you all is of hope, courage and confidence. Let us mobilise all our resources in a systematic and organised way and tackle the grave issues that confront us with grim determination and discipline worthy of a great nation.”

—Nabiha Gul is Cooperative Lecturer at the Department of International Relations, University of Karachi.

“There is no power on earth that can undo Pakistan.”

(Speech at a mammoth rally at the University Stadium, Lahore on October 30, 1947)

Jinnah’s Pakistan: an integrated nation

By Muttahir Ahmed Khan

Truly speaking, if Quaid-i-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah had been present amongst us today he would have been extremely grief-stricken to see his nation falling prey to the fatal diseases of disunity, disharmony and disintegration. The whole voyage of the great leader’s struggle for a separate homeland for the Muslims of the subcontinent was based on the pivot of Muslim unity and oneness as a nation, without any thought of ethnic, lingual or sectarian discrimination. Addressing a public meeting at Dacca on March 21, 1948, Mr Jinnah clearly warned: “Let me warn you in the clearest terms of the dangers that still face Pakistan. Having failed to prevent the establishment of Pakistan and thwarted and frustrated by their failure, the enemies of Pakistan have now turned their attention to disrupt the State by creating a split amongst the Muslims of Pakistan. These attempts have taken the shape principally of encouraging provincialism. As long as you do not throw off this poison (of provincialism) from our body politic, you will never be able to weld yourself, mould yourself, galvanise yourself into a real, true nation. What we want is not to talk about Bengali, Punjabi, Sindhi, Baluchi, Pathan and so on. They are, of course, units. But I ask you: have you forgotten the lesson that was taught to us thirteen hundred years ago? If I may point out, you are all outsiders here. Who were the original inhabitants of Bengal? Not those who are now living here. So what is the use of saying, ‘We are Bengalis or Sindhis or Pathans or Punjabis.’ No, we are Muslims.”

nation falling prey to the fatal diseases of disunity, disharmony and disintegration. The whole voyage of the great leader’s struggle for a separate homeland for the Muslims of the subcontinent was based on the pivot of Muslim unity and oneness as a nation, without any thought of ethnic, lingual or sectarian discrimination. Addressing a public meeting at Dacca on March 21, 1948, Mr Jinnah clearly warned: “Let me warn you in the clearest terms of the dangers that still face Pakistan. Having failed to prevent the establishment of Pakistan and thwarted and frustrated by their failure, the enemies of Pakistan have now turned their attention to disrupt the State by creating a split amongst the Muslims of Pakistan. These attempts have taken the shape principally of encouraging provincialism. As long as you do not throw off this poison (of provincialism) from our body politic, you will never be able to weld yourself, mould yourself, galvanise yourself into a real, true nation. What we want is not to talk about Bengali, Punjabi, Sindhi, Baluchi, Pathan and so on. They are, of course, units. But I ask you: have you forgotten the lesson that was taught to us thirteen hundred years ago? If I may point out, you are all outsiders here. Who were the original inhabitants of Bengal? Not those who are now living here. So what is the use of saying, ‘We are Bengalis or Sindhis or Pathans or Punjabis.’ No, we are Muslims.”

He further said, “While, however, one must love one’s town and work for its welfare-indeed because of it-one must love better one’s country and work more devotedly for it. Local attachments have their value but what is the value and strength of a ‘part’ except within the ‘whole’.” Had we paid heed to his warnings and advice we would not have got entangled into provincial politics that have brought forth further ethno-lingual divisions within the provinces. Even a cursory glance at our contemporary socio-political scene and morals can lay bare the bitter fact that we are undergoing a severe and critical phase of our national history that is fully tarnished with ethno-lingual prejudices, socio-economic classification and sectarian divides. Words like “All the Muslims are united as one nation under the banner of Islam and Allah” seem to be only mythical references and fabulous ideas. On the one hand, due to our diabolical political maneuverings, we are suffering from the plague of provincialism, regional politics, ethno-lingual hostilities and are being hit in the chest by the mighty blows of sectarian violence and religious extremism, on the other.

The situation in the province of Baluchistan, in regard to secessionism, is very grave although it is not adequately highlighted by the media and the press. The grievances of the Baluchis are not new and can be traced to the pre-partition period. Addressing the people of Quetta in 1948, the Quaid expressed his concern about the province, saying, “As you all know I am especially interested in Baluchistan because it is my special responsibility. I want to see it play as full a part in the affairs of Pakistan as any other province, but it will take time to remove the symptoms of long neglect. In order that this time may not be a minute longer than necessary, I earnestly request you to co-operate with me, to give me your selfless support and not to make my task difficult.” Unfortunately, the father of the nation could not have enough time to materialise his desire and the issues began to grow bigger and bigger with every passing year due to successive incompetent and selfish rulers.

Since the death of the Quaid, our pseudo-intellectuals and half-baked scholars, impelled by political and theocratic miscreants, have been trying to fallaciously prove the Quaid either a theocrat or a totally non-religious and secular figure by creating two mutually diverging extremes of their own. Our great father was a man of wisdom, intellect, prudence and deep insight and, therefore, could not be believed to possess any extreme approach regarding humanity and nation building.

The Eid message, he delivered in September 1945, is a vivid path to lead us to his balanced approach and moderate views and removes all doubts about his association with and understanding of the religion. He said, “Everyone, except those who are ignorant, knows that the Quran is the general code of the Muslims. A religious, social, civil, commercial, military, judicial, criminal, penal code, it regulates everything from the ceremonies of religion to those of daily life; from the salvation of the soul to the health of the body; from the rights of all to those of each individual; from morality to crime, from punishment here to that in the life to come, and our Prophet (PBUH) has enjoined on us that every Musalman should posses a copy of the Quran and be his own priest. Therefore, Islam is not merely confined to the spiritual tenets and doctrines or rituals and ceremonies. It is a complete code regulating the whole Muslim society, every department of life, collectively and individually.”

We must endeavour to understand the very essence of our nation state conceived by the Quaid. So far as our father’s concept of constitutional development is concerned, he expressed his views saying, “I do not know what the ultimate shape of this constitution is going to be, but I am sure that it will be of a democratic type, embodying the essential principles of Islam. Today, they are as applicable in actual life as they were 1,300 years ago. Islam and its idealism have taught us democracy. It has taught equality of man, justice and fair play to everybody. In any case Pakistan is not going to be a theocratic State to be ruled by priests with a divine mission. We have many non-Muslims - Hindus, Christians, and Parsis - but they are all Pakistanis. They will enjoy the same rights and privileges as any other citizens and will play their rightful part in the affairs of Pakistan.” (Broadcasted address of Jinnah to the people of the United States, in February 1948).

caption

Quaid-i-Azam meeting supporters at Quetta Railway Station in 1945

QUAID-I-AZAM AS GOVERNOR GENERAL OF PAKISTAN

Dr M Yakub Mughul

The Quaid-i-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah was one of the greatest leaders of the modern age. He not only led his people to independence but founded a separate homeland, where they could mould their lives in accordance with the traditions of Islam and cultivate their culture and civilisation. This was a far greater achievement of the Quaid than any other national liberation leader. Other leaders struggled for independence within states already in existence whereas the Quaid alone sought a separate homeland where none had existed. This he achieved almost single-handedly and constitutionally and in the teeth of opposition.

founded a separate homeland, where they could mould their lives in accordance with the traditions of Islam and cultivate their culture and civilisation. This was a far greater achievement of the Quaid than any other national liberation leader. Other leaders struggled for independence within states already in existence whereas the Quaid alone sought a separate homeland where none had existed. This he achieved almost single-handedly and constitutionally and in the teeth of opposition.

Pakistan’s emergence was not just the emergence of a new State. It was created on the basis of Islamic ideology. Had Pakistan not been created, the Muslims would have been under the subjugation of militant Hindu majority in the united India and would have lost their identity in the Hindu majority.

The Quaid-i-Azam, in his presidential address, at the special Pakistan Session of Punjab Muslim Students’ Federation on 2nd March 1941 said:

“We are a nation. And a nation must have a territory. What is the use of merely saying that we are a nation? Nation does not live in the air. It lives on the land, it must govern land, and it must have territorial state and that is what you want to get.”

The Quaid-i-Azam at the All India Muslim League session at Lahore on 23rd March 1940 discussed this point and said:

“I may explain that the Musalmans, wherever they are in a minority, cannot improve their position under a united India or under one Central government. Whatever happens, they would remain a minority, by coming in the way of the division of India they do not and cannot improve their own position. On the other hand, they can by their attitude of obstruction, bring the Muslim homeland and 60,000,000 of the Musalmans under one government, where they would remain no more than a minority in perpetuity”.

On 14th August 1947, with the efforts of the Quaid-i-Azam and his associates, Pakistan emerged as an independent Muslim State and on 15th August Quaid-i-Azam was sworn in as its first Governor General.

His nomination to the exhaled position of Governor-General was an event of great rejoicing for the Muslims of India which created tremendous impact on the national and international situation. In fact, it was the recognition of his sincere services for the cause of Pakistan.

His elevation from the Quaid-i-Azam to Governor-General of Pakistan enhanced his personal, political and official reputation amongst his great contemporaries. His contribution as Governor-General should be visualised in the background of extraordinary conditions created by the partition of India. His mere presence as the Head of State was enough to create a psychological impact on the Muslims of Pakistan who were inspired by his leadership and dynamic personality.

The Constituent Assembly resolved that Mohammad Ali Jinnah, President of the Constituent Assembly of Pakistan and Governor-General designate of Pakistan be addressed as “Quaid-i-Azam” Mohammad Ali Jinnah, Governor-General of Pakistan in all official Acts, documents, letters and correspondence from 15th August 1947.”

The Quaid appointed Nawabzada Liaquat Ali Khan, his lieutenant in the political struggle and General Secretary of All India Muslim League, as the Prime Minister of Pakistan. In the first cabinet the Quaid nominated political stewards like Abdul Rab Nishtar from NNWFP, who was placed in charge of the Ministry of Communications, Fazlur Rahman, a leading politician from East Pakistan was given the Ministry of Education and Information, I I Chundrigar, a lawyer who had distinguished at Delhi, was given the Ministry of Commerce, Ghazanfar Ali Khan from the Punjab, agriculture and health. Ghulam Muhammad, though no Leaguer, was given the portfolio of Finance on account of his expertise in finance. Outside the cabinet, Sir Zafarullah Khan became Foreign Minister, who had an outstanding record of judicial service, was also deputed to represent Pakistan at the United Nations.

Jogendra Nath Mandal, a scheduled caste leader from East Pakistan, was given the Ministry of Law, Labour and Construction in the Federeal Government.

Above them all stood the towering and magnetic personality of the Quaid, the Founder of Pakistan and Father of the nation.

The Quaid-i-Azam, Governor-General of Pakistan in a message to the nation said on Friday 15th August 1947:

“Pakistan is a land of great potential resources. But to build it up into a country worthy of the Muslim nation we shall require every ounce of energy that we possess and I am confident that it will come from all whole-heatedly.”

The Quaid after resuming charge of the Governor-General of Pakistan became the powerful head of State because he was at the same time Quaid-i-Azam, the Great Leader, the Creator of Pakistan and Father of the Nation. He appointed members of the cabinet and presided over its meetings. Pakistan at the time of independence needed its Founder as its Governor-General. Moreover, the Cabinet by a resolution had also authorised him to exercise all these powers on its behalf. He could overrule the Cabinet. He had, again by a Cabinet resolution, direct access to all the Secretaries and all the files. He also took the portfolio of the ministry of refugees in his hands in order to solve their problems on top priority basis.

When Pakistan came into being, the Quaid-i-Azam was sick and exhausted physically, but in-spite of that he devoted his energies and worked day and night for the newly-created country - Pakistan, so that it should stand on sound footing.

As Governor-General of Pakistan, the Quaid-i-Azam was confronted with the onerous task of organising the newly-born State a new and afresh from top to bottom.

The Quaid-i-Azam was fully conscious that partition would leave minorities in both states, but in one Muslims would be dominant and in the other Hindus.

It was the division of the Punjab that did the greatest harm to Pakistan. Three rich tehsils of Gurdaspur district with a Muslim majority were handed over to India, thus allowing India access to Kashmir, which had not yet decided whether to accede to India or Pakistan. The Kashmir problem, which is now called the unfinished agenda of partition, became a constant cause of concern for Quaid-i-Azam.

About 12 million Muslims were uprooted from their homes in India and were compelled to migrate to Pakistan to seek refuge and re-settlement. The refugees coming from India created many new problems for the government of Pakistan which were amicably solved. On the administration side, the offices were without staff and furniture, railway stations were badly damaged and other innumerable rehabilitation problems were afoot. Above all, the resources were limited but very soon new resources were discovered, taped and exploited to cope with all the problems.

Jinnah’s position as Governor-General of Pakistan was unique. He could not obviously fit into the traditional pattern of a ceremonial Head of the State. As the Founder of Pakistan, he occupied a position reserved only for the Father of Nation. He was no doubt above any office which the country could offer him.

Stanley Wolpert commenting on the achievements and great historical role of Muhammad Ali Jinnah, the great Quaid and Founder of Pakistan, remarked:

“Few individuals significantly alter the course of history. Fewer still modify the map of the world. Hardly anyone can be credited with creating a Nation-State. Mohammad Ali Jinnah did all three. Hailed as a ‘Great Leader’ (Quaid-i-Azam) of Pakistan and its first Governor-General, Jinnah virtually conjured that country into statehood by the force of his indomitable will.”

The Quaid-i-Azam was an indefatigable political leader. It was due to his honest and sincere approach that he was able to carve out the sovereign State of Pakistan, despite so many obstacles and impediments.