|

|

| |

|

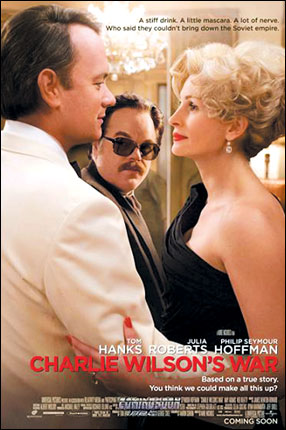

Charlie Wilson's War**

*ing: Tom Hanks, Julia Roberts, Philip Seymour Hoffman

Directed by Mike Nichols

Tagline: A stiff drink.A little mascara. A lot of nerve.Who said

they couldn't bring down the Soviet Empire

|

| |

In

a secret CIA ceremony in the 1990s, a Democratic Party Congressman

from Texas is being honoured for his role in delivering a "lethal

body blow to Communism." The agency is celebrating the "defeat

and break-up of the Soviet Union" - one of the "great events

of the 20th Century."

So begins the new Mike Nichols movie, Charlie Wilson's War. Starring

Tom Hanks, Julia Roberts and Philip Seymour Hoffman, the film bills

itself as the real story of how in the 1980s, a hedonistic politician,

Charlie Wilson (Hanks), conspires with an extreme right-wing Houston

socialite, Joanne Herring (Roberts), and an untamed CIA agent, Gust

Avrakotos (Hoffman), to conduct the largest US covert operation in

history: the securing of money and weapons for the fight of the Afghan

"freedom fighters" against the Soviet army.

Nicholas's film, saturated with ferocious anti-communism, is a defense

of neo-colonialism and the right of American "democracy"

to intervene wherever it likes around the globe. And in some ways

it is an eye opener. All the congressional dealings and the power

US congressmen and senators have is mind boggling. Third world senators

are barely able to push around a few million dollars, while their

US equivalents are dealing in the billions.

|

|

| |

But

of course we know that Charlie Wilson and America never thought of

the consequences (or more likely, didn't care) of directing billions

of dollars worth of arms and training thousands of mujahideen. Charlie's

War not only drove the Russians out of Aghanistan, but destroyed both

Afghanistan and almost Pakistan in the process. If you are of Afghani

or Pakistani origin Charlie Wilson's War will make you angry.

No reasonable person expects a film, any film, to capture the intricacy

of real events with absolute accuracy; adaptations are translations,

and as the old Italian saying goes, "The translator is a traitor."

It's one thing to compress, combine and fictionalize a story to fit

the sprawling, ugly mess of it onto the big screen; it's another to

take only the best, shiniest parts of a real, ugly story and turn

it into a feel-good comedy. Translation may be treacherous, but Charlie

Wilson's War feels like a conscious act of treason against reason

itself. As film critic David Thompson has said, "We learn our

history from movies, and history suffers." Charlie Wilson's War

isn't just bad history, it is even more harmful; a conscious attempt

to induce memory loss. |

| |

Congressman

Charlie Wilson had as much fun with his position as you could, which

was a lot and the film focuses on that. So we see Charlie hot-tubbing

in a Vegas hotel suite, the room's full of booze, broads and blow.

But Charlie, played by Tom Hanks, can't look away from the news, as

one of his new acquaintances notes her apathy to world events, Charlie

boils it down: "Dan Rather's wearing a turban; you don't want

to know why?"

Dan Rather is in a turban because he's in Afghanistan, among the Afghan

mujahideen, the Islamic rebels trying to drive the Soviet Union out

of their country by any means necessary. This sight sparks something

in Charlie, so he sets out to increase CIA's funding for the Afghan

rebels, from 5 million dollars a year to 10.

|

|

| |

Charlie's desire to help puts him in contact with other likeminded

Americans, like Joanne Herring (Julia Roberts), a Houston socialite

whose Christian beliefs mean she'll support anyone against the Godless

communists, and Gust Avrakotos (Phillip Seymour Hoffman), a CIA man

who's not a company man. Joanne and Gust can't imagine anything worse

than the Soviets capturing Afghanistan, and they work with Charlie,

funneling money and arms through Pakistan, working with a motley crew

of arms dealers, spies, Saudi billionaires, Pakistan's military dictator

and other interested parties. Eventually, the covert funding to help

the mujahideen, with no Congressional oversight outside of closed

committees, was as high as a billion dollars a year in the name of

expelling the Soviets from Afghanistan.

And Charlie Wilson's War makes all that ugliness look like great fun,

hard-drinking, gladhand gestures. It may be so for the, but it is

sneaky spy stuff for anyone in this part of the world. What isn't

on screen in Charlie Wilson's War is any mention of the fact that

the Afghan mujahideen became the Taliban, or how the Afghan mujahideen

were helped in their cause by the Afghan Arabs who later became Al-Qaeda.

That has to be the miss of the century as far as cinema is concerned.

The finale is a closing quote from Charlie, " we f***ed up the

endgame" seems to imply that Mr. Wilson's actions led to 9/11,

but the link remains vague. There are fewer and fewer students of

history nowadays; more people will see this film than will ever read

George Crile's book. And while Charlie Wilson's War notes that Wilson

and his crew goofed up the 'endgame', what it doesn't quite acknowledge

is that for thousands of Afghans who suffered under the Taliban and

the armed forces of America and her allies in Afghanistan, it wasn't,

and isn't, a game. It's a reality that gets harsher by the minute.

Instead of acknowledging that, Nichols offers us champagne-sparkle

charm and whimsy. If a film really wants to tackle the covert actions

of the Cold War and their long-term consequences, it needs to provide

short sharp shots of truth as raw as straight up whiskey, one after

the other. We get the busy boozy buzz of Charlie's crusade; what Nichols

has done is eliminated the historical hangover of unintended consequences.

Charlie Wilson's War is timid where it should be reckless, clever

where it should be cutting, funny where it should be fierce.

"Zia ul Haq did not kill Bhutto." Those words are spoken

by Julia Roberts introducing the new President of Pakistan. That Charlie

Wilson's War was released after Benazir Bhutto's assassination bears

testimony as to how relevant those events remain to Pakistan's reality.

Charlie Wilson's War should have been a film about how every event

has consequences, and how one good thing does not necessarily mean

everything is hunky dory in the long run. But it is a decadent portrayal

of an American Congressman and his cronies who decided to play God.

To top it off, the film is historically inaccurate. During the '80s

everyone knew the US was fighting a proxy war in Afghanistan. During

the Cold War era, the US was not going to allow Soviet influence to

spread uncontested. Charlie Wilson's War would have us believe that

Wilson was solely responsible for our covert operations over there.

This simply isn't true. He may well have organized the political effort,

but if he didn't, someone else would have. Not to mention, that the

film makes it seem like all the rebels needed was stinger missles

and overnight they were saved; in fact there's a lag time of about

eight years, and they received a lot more help than just the ability

to shoot down choppers.

However, the OTT Charlie Wilson claims credit for everything in this

film. And he does this while drinking to excess and partying with

strippers. He even gets out of an ethics jam when a witness claims

he snorted cocaine in the Caymans, outside of the Justice Dept jurisdiction

(in a case brought by then federal prosecutor Rudy Giuliani). When

he goes to Pakistan to meet with the new President (Zia), and later

to a Peshawar refugee camp, he is spurred to action.

There is little opportunity here to give the devil his due. Some of

the scenes are amusing, for example one in which he deals with a rich

Christian diehard who tries to get Wilson to support the placing of

religious icons in public venues. However, considering the glittering

calibre of talent on screen and behind the camera, Charlie Wilson's

War is a disappointment. We haven't really spoken about the performances

in the film, because they're largely irrelevant. Hanks is miscast

as a Texan; Roberts is, as always, herself; Hoffman gets to rage,

but his character's deeper doubts are shoved off-screen for wacky

globetrotting adventures on the part of Hanks and Roberts.

This movie wants to be a funny, yet cautionary political satire but

just winds up as a waste of Hollywood resource. Nichols peppers the

film with sex, beautiful women, booze and smoking, in a desperate

effort to make it seem subversive and carefree, but it's all too carefully

calculated. The film plays with scene after scene of talk, talk, talk,

while Nichols makes sure the actors are sitting in really interesting

rooms. Indeed, the entire story is passed back and forth through the

mouths of characters, rather than anything visual, and the key scene,

in which the Americans visit the Afghani refugee camp nearly blows

the whole deal; it looks like a Hollywood backlog with well-fed extras

dressed in robes. And it just doesn't strike a chord for us who know

what Afghan refugees actually looked like.

Although Nichols is legendary for his skill with actors, the problem

is that in his latest work the performers are required to derive inspiration

from a script that is untruthful and deliberately constrained. That

is a problem. How are actors to present short visioned reactionary

people as intriguing, even progressive? How is one to empathize with

an individual who includes a hated, brutal ruler as part of his inner

circle? And what about transforming a twisted, bloodthirsty CIA agent

and a fundamentalist aristocrat into political role models? On the

other hand, no effort is spared to portray the film's only Russian

characters, two pilots who engage in banter as they prepare to shoot

down Afghans, as heartless brutes.

It's difficult even for someone with Nichols' talents to bring together

the image of a rebellious, good-hearted lawmaker with that of a conspiratorial

law-breaker whose actions have led to a nightmare for the Afghan,

Pakistani and American people. Nichols ends his movie with a comment

from Wilson on screen: "These things happened. They were glorious

and they changed the world. And the people who deserved the credit

are the ones who made the sacrifice. And then we f***ed up the endgame."

Of what use such allusion when as history, Charlie Wilson's War is

a travesty? Nichols and his screenwriter, Aaron Sorkin, have made

an effort to take advantage of the general low level of historical

knowledge to transform an imperialist provocation into a fight for

freedom. The film ludicrously claims the US intervention in Afghanistan

owes its origins to a hot tub in Las Vegas from which Wilson, playing

around with strippers and call girls, sees a television broadcast

of Dan Rather in the Afghanistan. In its effort to glorify Charlie

Wilson as the savior of the Afghan people, who are scarcely present

in the film, the film omits a few inconvenient facts.

The maverick congressman came onto the scene well after the Democratic

administration of Jimmy Carter had decided to give financial and military

support to the Islamists engaged in guerilla warfare against the Soviet-backed

regime in Kabul, which had come to power in a military coup in 1978.

This preceded the Soviet invasion of the country in 1979.The Carter

regime, which hoped a war in Afghanistan would be the USSR's Vietnam,

began funding and arming the most right-wing fundamentalists, the

ancestors of the Taliban and Osama bin Laden. Neither does the film

mention that Carter's successor, Ronald Reagan, was an enthusiastic

promoter of the fundamentalists and that his CIA director, William

Casey, is deserving of the title "founding father" of Al–Qaeda

for his campaign of globally recruiting Islamic militants to come

to Afghanistan to fight the anti-Communist cause. (Carter's national

security advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski gloated in a 1998 interview that

some "stirred-up Moslems" were a small price to pay for

the collapse of the Soviet Union, the "liberation of Central

Europe and the end of the Cold War.")

Far from being an unsung champion as Nichols would have it, Wilson

was a pawn on the global chessboard, a bagman for those responsible

for nearly two decades of civil war and the destruction of Afghan

society.

The unseriousness and dishonesty of the Nichols-Sorkin project are

breathtaking. The film's publicists dreamt up this crude tagline:

"A stiff drink. A little mascara. A lot of nerve. Who said they

couldn't bring down the Soviet empire?"

Charlie Wilson's War is not simply a justification of the Afghan operation;

it can be interpreted as a blank check for any present and future

military action by the US.

As far as one can make out, Nichols is making an argument along these

lines: Wilson was something of a disreputable figure, some of his

associates were even worse, but, in the end, their collective effort

resulted in a positive development.

Nichols explained in an interview posted at thedeadbolt.com, he was

drawn to the project by the unlikely manner in which people's liabilities,

or elements of them, become assets: "And it is what finally draws

you to most drama, which is that it's the unexpected things about

people, in fact in life, even. The unexpected things that seem to

be drawbacks that are somehow transformed into the better qualities."

This is so absurd. Not every unexpected outcome is possible. A pencil

can't become a carrot. An operation that began as an illegal political

provocation, aimed at advancing US geopolitical interests, couldn't

be transformed into a struggle for any people's freedom. Hollywood

has turned a sharp-toothed, snarling real story into a neutered, nuzzling

house pet. Ultimately the film offers the bright glare of star power

instead of any real illumination and as far as comedies go, Charlie

Wilson's War stops being funny when you realize we're living in the

sequel.

– Saba Sartaj K

*YUCK

**WHATEVER

***GOOD

****SUPER

*****AWESOME |

| |

|