1.6180339887. That is what Mekaal Hasan - the musician and producer is: the golden ratio. And if it seems too clinical to reduce a man to a bunch of numbers, allow me to elucidate. 1.6180339887. That is what Mekaal Hasan - the musician and producer is: the golden ratio. And if it seems too clinical to reduce a man to a bunch of numbers, allow me to elucidate.

Mekaal Hasan seems to have this whole perfection thing going on for him, which might not make him seem too exciting, and probably inspires thoughts of him sitting in his studio planning the next melody he will mix flawlessly, but that also is just reducing him to mere adjectives. When one comes across someone who commands instant awe or immediate wariness, both thanks to the abovementioned attributes, and seems to actually be quite … not what you expected, how do you describe him?

Over the years, much has been written about Mekaal Hasan, brain behind the Mekaal Hasan Band (MHB) and funnily enough, the hand behind many a musical production in the last couple years. It seems almost silly to say something about the musician; as there is nothing that he hasn't been interviewed about in the last decade, printed in magazines and papers, and republished on the web. Mekaal Hasan was a Jazz Composition major at Berkley College of Music. But you already knew that didn't you? You too, like thousands of other people probably read about Mekaal in these very pages in 2001 and thought to yourself, "Wow, this guy sounds like he knows what he's doing, I wonder when his album will come out?"

That album, Sampooran, in 2004, came out about three years later, and by that time, the Mekaal Hasan Band collectively had established themselves as very serious about music and very serious about life with their first video that had an impact, 'Rabba'. Mekaal, being the leader of the pack, had earned himself the image, for his audience at least, of someone who very quietly sat back in the shadows in the band's videos and played his music, well, very seriously. Plus anyone who answers a question asking for a music tip with a sharp reminder of a musical career not reaping instant rewards, and anyone looking for the same should "work in a bank or something" (Karachi Underground 2002-2003), will scare future hopeful questioners into never approaching him with one.

It was with a certain lingering trepidation of being looked down upon by Mekaal Hasan's highbrow-ness that one asked him a bunch of things, and was quickly taken aback and delighted by turns to discover that Mekaal is pretty normal. He actually smiles often and is quite fun to speak to. Sometimes it almost feels like he is Google and might just have the answer to everything in the world, but that is reassuring too, because for once the self-assured vibe is coming off someone who has earned it and is not just talking out of his self-important behind.

"The good thing about learning it that way," says Mekaal of music production, "the hard way, is that you learn how everything works." Mekaal had started learning how to mix music before the advent of software that could aid and make his life easier. "I had to learn on a mixing board," he recalls, "and I had no clue what the hell all those knobs and those buttons were. And I just sat there and learnt it by making mistake after mistake."

From 1995, the technology-less year Mekaal speaks of to 2003, it seems as though all the mistakes had paid off. 'Rabba' as mentioned earlier was an intense song; haunting all round aurally and visually. After all, a man with the world literally resting atop his shoulders, almost tangibly bummed out even with the paper sculpture covering his face, as one of the melancholic songs in that particular genre that year played behind him, had to leave a lasting impression.

"That whole video was about ostracization," Mekaal explains, "of people feeling like they don't belong and how people treat them if they are different."

Interestingly, when Mekaal helpfully explains the 'Chal Bulleya' lyrics, the video of which had a wide audience captured with its intriguingly evolved storyline, the protagonist of the song (which is Bulleh Shah for the first four lines, Bhagat Kabir for the next four) is asking to a place where he can't be seen, or boxed into a certain slot or acknowledged as anything at all. The theme of a yearning for the blurring of differences that make people unique seems to be recurrent, and one can't help but ask Mekaal if it is a theme that is consciously implemented. Especially as paradoxically the 'Chal Bulleya' video seems to have a sort of judgmental twist to it. Mekaal doesn't agree. "I wanted to do something that was fun, but dark not morose. Basically all these characters are doing excessive stuff, we're not saying it's bad," Mekaal elaborates, "we're saying it's excessive."

Photos by Maram & Aabroo

Mekaal's wardrobe by Ammar Belal

For the 'Chal Bulleya' video, Mekaal had wanted to play with Tarantino's Four Rooms concept - different spaces connected by one person. The concept got expanded into the seven sins by director Bilal Lashari, with little daubs of symbolism all over the video for those who could spot them. For instance, the 'lust' bit is the one with the flute solo. The flute was "Pan's instrument, the instrument of lust" in Greek mythology and in the absence of any other possible depiction of that particular sin; musical innuendo had to suffice in the room of lust. Mekaal points all these details out, explaining how the video was tweaked to that exact ratio of just right, exactly as the music he makes, or the albums he produces for other artists are. "Depending on the kind of music you want to record, your engineering technique evolves with that as well," he says. "You can't apply the same formula to each recording – every recording is different." For the 'Chal Bulleya' video, Mekaal had wanted to play with Tarantino's Four Rooms concept - different spaces connected by one person. The concept got expanded into the seven sins by director Bilal Lashari, with little daubs of symbolism all over the video for those who could spot them. For instance, the 'lust' bit is the one with the flute solo. The flute was "Pan's instrument, the instrument of lust" in Greek mythology and in the absence of any other possible depiction of that particular sin; musical innuendo had to suffice in the room of lust. Mekaal points all these details out, explaining how the video was tweaked to that exact ratio of just right, exactly as the music he makes, or the albums he produces for other artists are. "Depending on the kind of music you want to record, your engineering technique evolves with that as well," he says. "You can't apply the same formula to each recording – every recording is different."

"With the recordings I do, the bands I work with," continues Mekaal, "I am very conscious of not making every band sound the same. We did Ali Azmat, Zeb & Haniya and Jal in the same months and those records will not sound like each other at all."

Happily enough, Mekaal is not just saying the records he produced for other artists that released between 2007 and '08 sound different. Where Zeb & Haniya's 'Chup' is mellow and luxuriously paced, Ali Azmat's Klashinfolk is glamourously rock & roll. And in the same breath, Jal's 'Boondh' is prettily pop-py. How does Mekaal the producer manage to jump between so many different sounds without mixing them up at least a little?

"It can be a challenge," Mekaal replies. "As at the end of the day you more or less have the same mics, the same rooms and the same musicians; the same people played on Ali's album that did on Zeb & Haniya's: Omran, Gumby and Mannu."

Like a thorough professional, Mekaal works though this challenge methodically. He avoids the evil of making one sound too similar to another by "working with references with them." "I always ask my client to give me musical references of what they want their song to sound like," Mekaal says. "We sit down in pre-production and listen to what their ideas are, and the kind of sound they are looking for."

"Ali was very insistent on doing a very Red Hot Chilli Peppers kind of sound," Mekaal cites an example. "I understood that the kind of sound he was looking for was more funk-driven, more rhythmic and more guitar based." Zeb & Haniya on the other hand came out with an "acoustic and ambient feel" in their music, Mekaal further explains, as they were more into the music of John Mayer, KT Tunstall and Nick Drake.

But when it comes to personal preference between artists he has produced for? "I like them all man," says Mekaal, "they're all good – sound tu sound hoti hai (sound is sound)."

"I think what bugs me is bad songwriting and then having to produce those records. I try not to do too many records that I don't like listening to. I have to mix it and it takes a lot of time."

Mekaal Hasan says that he has no particular preference for a certain genre of music either; for him it depends all on the performer. For Mekaal, bad artists can screw up any kind of genre.

He does like it though if the people coming to him have some idea of what they want. "If someone walks in and they are clueless, and say, 'Aap mujhay hit gaana bana dein' (make me a hit song) and I'm like, what do you mean, hit gaana bana dein?!" He does like it though if the people coming to him have some idea of what they want. "If someone walks in and they are clueless, and say, 'Aap mujhay hit gaana bana dein' (make me a hit song) and I'm like, what do you mean, hit gaana bana dein?!"

Does he actually get requests like that? "Yes, lots," confirms Mekaal. And does he take them on? "No," he replies instantly, laughing. "I've had to mix a few songs where I didn't want to, because of the money thing," says Mekaal as an afterthought. "If you start turning down everyone then people won't come to you at all."

"You do end up in sessions where you're like, 'this is hopeless, but I have to mix this'. You do that. And I've done that. But I try to restrict myself to not doing it."

But for any artist (any discipline) there does come a point where it strikes them that they're investing their own money into a projects or projects which may or may not reap monetary returns. Is money hard to come by for artists in Pakistan?

"These days it is exceptionally bad," Mekaal says immediately. "Right now it's so bad; I haven't seen this kind of inactivity in the music scene in 10 years. During Musharraf's era it was pretty good. There were plenty of shows, lots of work. Even people who weren't doing that well still had work. At the moment even our top acts are sitting at home."

The only way Mekaal sees out of this slump is by playing the international festival circuit and establishing the Pakistani music presence internationally. "That is the only way we can develop a market outside of Pakistan," Mekaal believes. "Because the only other option we are left with is India and that isn't a viable option for anyone because all they want is music for Bollywood, and once they've bought your songs, they're going to sell them and you're still going to be sitting here. You can't go there because they won't give you a visa!"

On the other hand Mekaal does think that the "world music market is a much more viable option", as people around the worked have become much more "interested in what Pakistani artists have to say and what kind of music and art we produce. There's a big market for Pakistani art as well."

While all of this does sound true and good, how does one go about it? "It's just a matter of our government being proactive and pushing our music and culture at festivals and cultural events abroad," say Mekaal, "which of course, our government has not being doing."

"We don't want money from them," Mekaal clarifies. All he thinks should do the trick is the government helping with visas and tickets, and perhaps appointing musicians and artists as "cultural emissaries."

While MHB does get invited to a lot of festivals abroad, these festivals don't have the cash to fly them in either. However, what these events can offer performers is "a lot of exposure – there is so much world media at these events that you can do a lot with just one show."

Mekaal points out that all artists from other countries who tour through Pakistan are cultural ambassadors for their countries, while at home, there exists no concept of the same. One wonders if all musician getting together and lobbies for help in reaching the international scene will work.

Mekaal disagrees. "Not all of our artists are interesting to the international market," he says. "Internationally, they will be more interested in Abida Parveen than Ali Zafar or Atif Aslam."

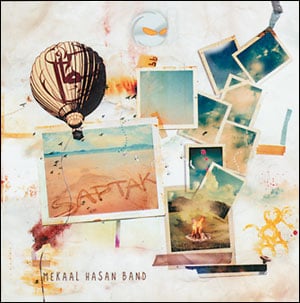

Mekaal Hasan sure doesn't mince words. So one is not surprised upon seeing the incredibly-more-thought-out-than-any-other album art for Saptak, the album which MHB just launched in Karachi officially. It is as painstakingly put together by Mehreen Murtaza as all the music we have heard from Mekaal Hasan to date. This obviously (only to me perhaps) raises a most important question: if Mekaal was a visual artist – what medium would he pursue?

"Definitely miniature painting," Mekaal shoots back – naming one of the most intricate and deliberate disciplines in eastern art. And that spirals us back to the golden ratio – the exact calculation of that which appeals most to the human aesthetic – and can be found in Mekaal's work in abundance. Exacting loveliness, measured precisely to the last note. |