Pakistan has a special bond with Germany, particularly on the intellectual and academic side; and Germany Institutions, cultural and developmental, operating in Pakistan have only furthered that bond. In that regard, Goethe Institute has been a constant and regularly holds events, screenings and symposiums that expose its members and event attendees to fresh ideas and provide the platform for a healthy exchange of thoughts and perceptions. Pakistan has a special bond with Germany, particularly on the intellectual and academic side; and Germany Institutions, cultural and developmental, operating in Pakistan have only furthered that bond. In that regard, Goethe Institute has been a constant and regularly holds events, screenings and symposiums that expose its members and event attendees to fresh ideas and provide the platform for a healthy exchange of thoughts and perceptions.

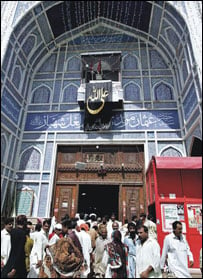

A recent event at the Goethe Institute was the screening of a documentary The Red Sufi, by Germany director Martin Weinhart. It is about one of the most popular Sufi saints of Pakistan, Lal Shahbaz Qalandar, who is also known as the The Red Sufi. Based on the book, At the Shrine of the Red Sufi: Five Days and Nights on a Pilgrimage in Pakistan, by German anthropologist Jurgen Wasim Frembgen, it is a representation of how the author views the annual Urs celebration of the famous saint.

The author has a deep love affair with Pakistan that started around 13 years ago, and he has been a regular visitor ever since. Much stronger and deeper is his affinity with Sufi traditions, and the Red Saint occupies a special place in his heart; with a large body of academic work to show for it in which he has studied the various folklore in Sufi traditions spanning nearly the entire breadth of the Muslim world.

But it is the Sufi traditions of Pakistan in which Frembgen seems to be best acquainted with. And it was to bring this understanding to the wider world, particularly the German public, that compelled him to write the book – in narrative form instead of another academic treatise, as he put it – that was published in December, 2008.

Following its publication, he was approached by Martin Weinhart, a German filmmaker, who expressed his desire to capture the experiences narrated in the book in the visual form. For Frembgen, it was another reason to make his favorite pilgrimage, this time accompanied by a crew led by Weinhart, who had already made a documentary on the pilgrimage to Maulana Jallaluddin Rumi’s shrine in Konya, Turkey.

This was Frembgen’s sixth visit, as he had first attended the Urs in August 2003, and was so enchanted by the whole experience that he visited it every year thereafter.

However, as Frembgen pointed out in his introductory speech before the screening, that the documentary only captured and manifested a very limited facet of spiritual Islam, which in itself is one facet of Islam. Furthermore, he pointed out that it was a subjective narrative, and documentation of things as seen through his eyes. He also touched upon the multiplicity of traditions and belief systems that exist within Sufism, and the difficulties in understanding – let alone visually representing – the same was a tall order.

Notwithstanding the initial disclaimer, the packed auditorium was looking forward to a riveting experience, seen through the eyes of a foreigner, though one who had a deep understanding of Sufi values and traditions through his corpus of work.

The documentary started off with the author in Lahore, from where he was to join a Kafla (procession) to the city of Sehwan in Sindh, where the annual Urs is held. The documentary started off with the author in Lahore, from where he was to join a Kafla (procession) to the city of Sehwan in Sindh, where the annual Urs is held.

In Lahore, he dresses in the traditional Pakistani attire of shalwar kameez, and has conversations with various vendors and shopkeepers who knew him from past visits. With commendable Urdu, he held spontaneous conversations with various people, including Faheem Mazar, a singer of the Khayal genre.

Faheem lamented the decline in his fortunes, attributing it to terrorist attacks, saying that he can only have small performances as anything on a large scale is a soft target. Reminiscing about better times, Faheem said that he used to perform before international audiences, but now, Pakistan has become Bomb-istan due to the Taliban, whom he referred to as Zaliman.

The author himself commented on this altered landscape, where the threat militancy had affected everyone, particularly after the attack on the Data Darbar in Lahore. Shots of policemen and security personnel are interspersed throughout the documentary and a constant reminder of the tenuous security situation.

The camera follows Frembgen to a market of knives and other objects used for flagellation, as he discusses sales and prices.

He also holds discussions with devotees of Lal Shahbaz, and the camera manages to capture a sense of euphoria that envelopes the walled city of Lahore in the build-up to the Urs.

Amid chants of ‘Hail the Red One’, he embarks on the journey to Sehwan in a train, as part of a Kafla. The music and joy played serves as a precursor of the delights to follow.

Once at Sehwan, he renews old acquaintances and makes new ones while the camera tries to capture the ecstasy and pleasure that envelope the devotees. But the trance-like state that is induced is a state of mind that is only partially, if at all, manifested physically.

To achieve this, the documentary is punctuated with shots of people dancing and whirling in a frenzied state, while the author quizzes numerous people about it. The responses were tepid, with his interlocutors, one of whom is a renowned for Dhamal, more interested in pointing out their stints with the film industry, rather than the spirit of ecstatic delight & stupor induced by being in close proximity with their patron saint.

The camera follows the author as he quizzes all kinds of people, including eunuchs, who say that they visit the shrine with almost religious fervor as the Red Saint provides for whatever they ask. Another young man, with over-grown hair and beard, calls the Urs a Pakistani version of Woodstock as he continues to smoke away and dance to the rhythmic beating of the drums.

Some of Frembgen’s older acquaintances also meet him warmly; and share with him anecdotal details that give some insight into the Sufi culture. He is also shown the image of one of the gaddi-nasheens (heir through linkage or keeper to the shrine), who had locked himself in a room for the last 26 years. Some of Frembgen’s older acquaintances also meet him warmly; and share with him anecdotal details that give some insight into the Sufi culture. He is also shown the image of one of the gaddi-nasheens (heir through linkage or keeper to the shrine), who had locked himself in a room for the last 26 years.

It’s the various meditative aspects that gave Sufis the popularity and earned them the devotion of hundreds of thousands of people. However, any insights on that is missing, as the filmmakers focus more on capturing the external manifestations of the sense of ecstasy and delight felt by the followers.

Another aspect through which the documentary tries to show the extent of devotion is that of Matam (self-flagellation), a practice of the Shi’ite faith, which is supposed to be their penitence and expression of sorrow over the martyrdom of their Imams.

Although the shrine is visited by people of all religions and sects, those of the Shi’ite faith are more prominent in their presence. Also, with Lal Shahbaz’s lineage linking him to one of the twelve revered Imam’s of the Shi’ite faith, the Urs serves as an opportunity for the sect’s followers to show their devotion.

Despite being an essential component of the devotional practices at the Urs, the scenes of self-flagellation – the rhythmic beating of chests, lashing of the back with knives – dominates the footage from the Urs. The sight of young men with their backs bleeding profusely adds an unnecessary element of blood & gore.

Along with that, the focus on intoxicants is another aspect that can very easily be misconstrued. While consumption of hashish is also a part of Sufi culture, its juxtaposition with ‘intoxication’ is erroneous. The Sufis message of intoxication implies the devotee being absorbed and intoxicated by the love of the divine. However, as depicted in the documentary, the non-discerning viewer is likely to assume that the intoxication refers to consumption of hashish and other drugs, which then results in the ecstatic state of mind, as opposed to it being inspired by feeling a sense of oneness with the divine love for the saint.

The excessive focus on self-flagellation and ambiguous representation of intoxication are not the only shortcomings the documentary suffers from. Scant attention has been paid to doctrine of Lal Shahbaz, with his teachings limited to ‘I know nothing except love, intoxication and ecstasy.’

This over-simplification of the teachings of the Red Saint is unacceptable coming from someone with such a deep and nuanced understanding of the Sufi culture – not just in Pakistan but across most of the Muslim world; and this was also pointed out in the Q&A session following the screening.

Despite the criticism, the documentary did have its positives, as one young viewer pointed out to this scribe, that she felt quite enlightened after the documentary as she knew next to nothing about this stream of Islam. Bilal, a young professional, pointed out that while what was depicted in the documentary was indeed how things occur at the Urs; however, there was much greater focus on Shi’ite rituals as opposed to how he saw the event during his visit a few years ago. Despite the criticism, the documentary did have its positives, as one young viewer pointed out to this scribe, that she felt quite enlightened after the documentary as she knew next to nothing about this stream of Islam. Bilal, a young professional, pointed out that while what was depicted in the documentary was indeed how things occur at the Urs; however, there was much greater focus on Shi’ite rituals as opposed to how he saw the event during his visit a few years ago.

But it was from the elders that the documentary came under scathing criticism. One lady said that not only was the documentary misrepresentation of Sufism, but was also offensive due to its excessive focus on the consumption of intoxication, which was not what Sufism preaches.

Another elderly gentleman said that it barely scratched the surface but added that he would reserve his judgment until he had read the book, giving a twist to the cliché, ‘never judge a book by its movie.’

But the most insightful of remarks came from a visitor from Berlin, Lisa, who said that she was disturbed, the excessive scenes of flagellation, and blood and gore. She pointed out that people in Germany already have a misguided perception of Pakistanis as terrorists and suicide bombers; and she fears the movie would add to that misconception by making them think that Pakistanis are also nutcases who like to beat themselves.

With the movie set to be shown on German television soon, Lisa’s fears are very relevant, as are the criticisms of those who found the documentary superficial or even offensive.

Maybe it was due to paucity of funds, as the author pointed out in his introductory address that raising funds for Pakistani projects has become difficult in Germany, or some other reason, but the documentary falls short of paying homage to the Red Saint. It is particularly disappointing as an academic of high repute, Jurgen Wasim Frembgen, was the protagonist of the project.

Sufism’s major divergence from orthodox Islam is its lack of emphasis on rituals; and this documentary reduces Sufism to rituals, a grave injustice to the teachings of the Red Sufi and his devotees |